8.3.1 State and trends

The state and trends of heritage across the ACT are assessed by looking at the number of historic, Aboriginal and natural heritage places and objects on the ACT Heritage Register, and by assessing trends in registration across this and recent reporting periods. Data on heritage registrations are supplied by ACT Heritage.

Overall heritage registrations

Currently, there are 495 places and objects on the ACT Heritage Register, comprising historic (44), natural (9) and Aboriginal (72) heritage. In addition, all Aboriginal heritage places and objects in the ACT are protected under the Heritage Act, regardless of whether they are listed on the register (see ‘Aboriginal heritage places and objects’, below). These are estimated to number around 3000 sites.

Nominations to the ACT Heritage Register have significantly decreased since the 2011 State of the Environment Report – from 283 to 130 nominations. This reduction is due to an audit conducted in 2012–13, which identified a large number of duplications and removed a number of nominations for places on National Land under the Australian Capital Territory (Planning and Land Management Act) 1988, where this Act may be applied only in limited circumstances.

In 2011–2015, a total of 51 heritage places and objects were registered (Table 8.1). This represents a rise in registration decisions since the 2011 State of the Environment Report (2007–2011), during which time 22 registrations were added to the ACT Heritage Register. A number of decisions were also made during the reporting period on whether or not to reject or receive nominations, or to provisionally register sites and objects. All decisions made are detailed in the ACT Heritage Council annex to the Environment and Planning Directorate’s annual report, which is available on the website.

The registration of the Gunghaleen School House in Lyneham was cancelled following the destruction of much of the site by fire in 2007. The schoolhouse was subsequently rebuilt, but, because new materials were used in construction and there was a slight variation to the original design of the building, the ACT Heritage Council determined that the place no longer met the required thresholds to be included on the ACT Heritage Register (ACT Heritage, pers comm, 31 March 2015).

Table 8.1 ACT Heritage Council registration decisions, 2011–2015

| Activity | 2011–12 | 2012–13 | 2013–14 | 2014–15 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Nominations rejected |

6 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

|

Nominations received |

13 |

5 |

2 |

2 |

|

Decisions to provisionally register |

26 |

4 |

6 |

15 |

|

Decisions not to provisionally register |

13 |

47 |

22 |

12 |

|

Decisions to register |

26 |

10 |

2 |

13 |

|

Cancellations |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

Source: Data provided by ACT Heritage

Examination of the ACT Heritage Register listing gives an overall view of the type and number of heritage places and objects known to occur in the ACT. This allows an assessment of the state of heritage in the ACT to the degree that, while something is registered, it is afforded protection. These indicators also allow an assessment of trends in numbers of registrations during and across reporting periods. However, the trending up or down of these numbers is not necessarily an indication of an improvement or decline in the state of heritage across the ACT, because the condition of heritage sites and places is not accounted for. Under the Heritage Act, the ACT Government is obliged to report on the condition of assets it owns every three years. Apart from these assets, the condition of heritage places and objects is not monitored, so no assessment of this can be made in this report.

Historic heritage places

According to the Heritage Assessment Policy 2015,12 to be listed for registration, a historic place or object needs to demonstrate (among other things):

- evidence of a significant past event or way of life

- associations to past phases or events

- that it is the only one or a rare example of its kind in the ACT and provides key information in understanding an important aspect of our history.

Our historic heritage encompasses both our early and relatively recent past as a city. For example, the Palmerville settlement in Giralang, constructed by George Thomas Palmer in 1826, remained a thriving community until 1877. The site of the settlement has been retained as a park reserve and still contains archaeological features from the original settlement.

Our more recent heritage tells a story of the growth of the modern city, recognising the social, domestic and planning aspects of our origins as the nation’s capital.13

Canberra’s early planners embraced the principles of the Garden City Movement,14 with its ideals of broad streets, large house blocks and the maintenance of views to natural assets. Parts of Canberra’s earliest suburbs – such as Ainslie, Forrest and Griffith – embody the Garden City ideals, and are included on the ACT Heritage Register as an example of the early trends in planning in the city. During the reporting period, the Swinger Hill Cluster Housing was also added to the ACT Heritage Register as an example of the first medium-density cluster housing in the ACT. It also represents an example of 1970s planning ideals. Guidelines were developed and released by the ACT Heritage Council for the Swinger Hill Cluster Housing in 2013 to guide conservation and appropriate management for the site.

The heritage-listed former Kingston Powerhouse has been transformed into the Canberra GlassworksPhoto: ACT Government

Why is this indicator important?

Historic heritage helps to tell the story of our growth as a city, from the early European settlers in the region to more modern developments. The placement of historic heritage places and objects on the ACT Heritage Register protects these places to preserve the heritage of the ACT for generations to come. (See Community case study 8.1)

Current monitoring status and interpretation issues

Places and objects with historic heritage value are placed on the ACT Heritage Register by the ACT Heritage Council. Once placed on the register, these places and objects are afforded protection under the Heritage Act.

Much of the registered historic heritage comprises private residences. Monitoring and compliance of the Heritage Act as it applies to these places is difficult due to the lack of access to private sites.

What does this indicator tell us?

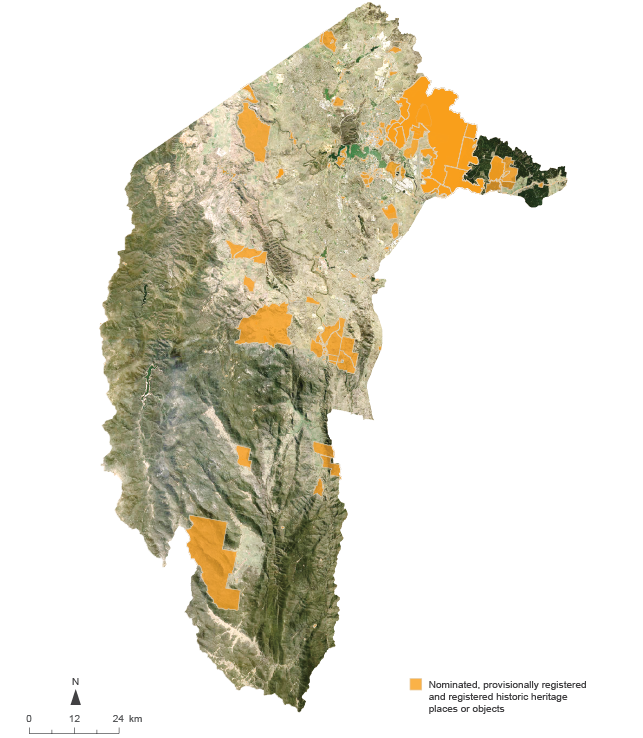

There are currently 414 historic heritage places and objects on the ACT Heritage Register (Table 8.2). These include buildings, objects and heritage precincts (Figure 8.1). A heritage precinct may contain several buildings and objects under the one listing. For example, the Garden City precinct will be shown as one listing but will cover each of the approximately 300 homes within the precinct, and any parkland, reserves and original street furniture.

In the 2011 State of the Environment Report, there were 142 places and objects registered as historic heritage and 207 nominated places. In 2015, there has been an increase in the number of registered places and objects, but the number of nominations has decreased. This is likely to be due to the audit carried out on nominations to the ACT Heritage Register, as discussed previously.

Table 8.2 ACT historic heritage places or objects, 2011–2015

| Activity | As at 30 June 2011 | As at 30 June 2012 | As at 30 June 2013 | As at 30 June 2014 | As at 30 June 2015 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Registered places and objects |

Unknown |

381 |

404 |

412 |

414 |

|

Provisionally registered places and objects |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Nominated places and objects |

201 |

184 |

139 |

113 |

88 |

Source: Data provided by ACT Heritage

Note: To protect restricted information, all areas have been enlarged to block boundary.

Source: Map provided by ACT Heritage

Figure 8.1 Location of historic heritage in the ACT

Community case study 8.1 In the trenches at Jerrabomberra Wetlands

WW1 trenches archeological dig at Jerrabomberra Wetlands. Photo: John Freeman

While preparing a history of the Jerrabomberra Wetlands Nature Reserve, early air photos of the reserve came to light with ‘strange squiggles’ on them. It turned out that this was the site of a trench warfare and bombing school – quite a find in the year of the centenary of World War I!

The trenches have long been filled in, but the Jerrabomberra Wetlands Management Committee recognised the potential of the site to generate community interest and further funding.

A collaborative project between the Committee, the Australian National University’s (ANU’s) School of Archaeology and Anthropology, and the ACT Parks and Conservation Service aimed to locate, protect, interpret and promote physical evidence of the Australian Imperial Force school.

A group of students from the ANU used ‘Time Team’ equipment to investigate the site, including ground-penetrating radar, magnetometry and resistivity testers. Unfortunately, this work proved largely inconclusive and more intrusive methods were required. The ACT Heritage Council approved limited excavation in the hope of intersecting some artefacts and gaining visual evidence of the 1916 trenches.

This work unearthed visual evidence of trench warfare training. When operational, the site contained a series of trenches used for different purposes such as supply, mortar bombing and front-line trenches. The trenches were constructed by soldiers from the Canberra region who were based at Goulburn at the time.

Other trench warfare training sites of this type in Australia have been lost to development, leaving the site at the wetlands as perhaps a lone example of this period in our history.

The sustainability of programs and funding is a concern for many conservation reserves, even those on public land. The Committee is hopeful that the discovery of the trenches will help to generate community interest and stakeholder engagement to support further research and development, and, in turn, support of conservation initiatives elsewhere within the wetlands.

Natural heritage places

Natural heritage places include places or objects that are considered to possess strong natural values. The Heritage Act defines a place as having natural heritage significance if it meets the following criteria:2

(a) forms part of the natural environment; and

(b) has heritage significance primarily because of the scientific value of its biodiversity, geology, landform or other naturally occurring elements.

(2) In this section:

‘natural environment’ means the native flora, native fauna, geological formations or any other naturally occurring element at a particular location.

Natural heritage in the ACT includes rare and unique examples of flora and fauna, and of significant landform features or landscapes. For example, the Hall Cemetery is registered as the location of the rare Tarengo Leek Orchid (Prasophyllum petilum; Chapter 7: Biodiversity) and the Tuggeranong Parkway cutting is a good example of the evolution of the ACT’s current landscape.17

Why is this indicator important?

Heritage registration of significant natural places affords protection to these sites so that our community may experience and learn from these unique places.18

Current monitoring status and interpretation issues

The amendments to the Heritage Act in September 201419 included a provision that the ACT Heritage Council cannot register a place or object that is, or is likely to be, the subject of a declaration under the Nature Conservation Act 1980. If the place also has cultural heritage significance or natural heritage significance of a kind not protected under the Nature Conservation Act, it may be included on the ACT Heritage Register. For example, the ACT Heritage Register currently includes two habitats with large populations of Button Wrinklewort (Rutidosis leptorrhynchoides), an endangered species of wildflower in the ACT (see Chapter 7: Biodiversity), where the purpose of protection is to ensure continued survival of the species. Under the amendments to the Heritage Act, these sites are unlikely to have been registered, because the populations would already be afforded protection under the Nature Conservation Act.

These amendments aim to ensure that there is no duplication between registrations under heritage legislation and under the Nature Conservation Act. It is anticipated that a number of the existing nominations for natural heritage places will not be entered on the ACT Heritage Register.

The amendments also clarified the registration of trees under the Heritage Act. The ACT Heritage Council may register an urban tree where it forms part of the heritage significance of the place, but not for the significance of the tree itself. This amendment is to eliminate duplication between the heritage legislation and the Tree Protection Act 2004.

All natural heritage places and trees currently on the ACT Heritage Register will remain listed under the Heritage Act. The amendments will only affect existing and future nominations to the register.

What does this indicator tell us?

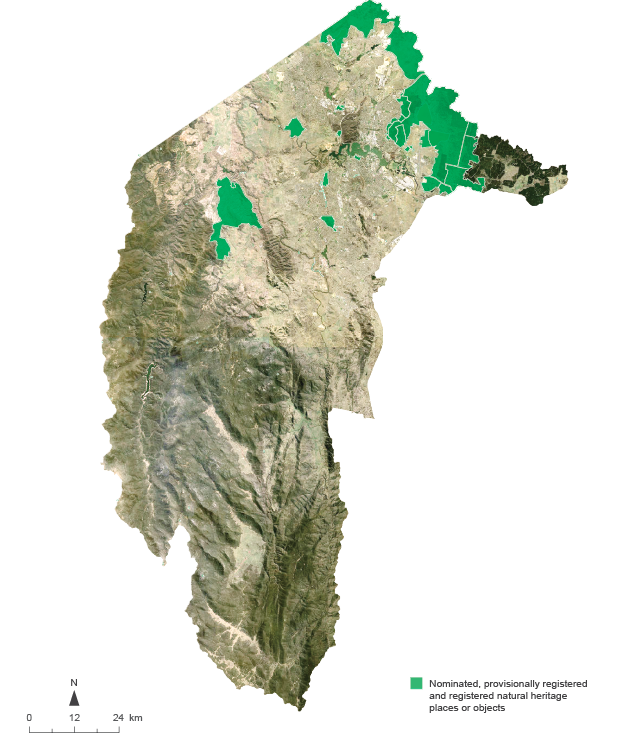

Currently, there are nine registered natural heritage places or objects on the ACT Heritage Register, compared with six registered at the end of 2011 (Table 8.3). Although the number of natural heritage places listed is quite small, the geographical coverage of these areas is relatively large (Figure 8.2). The natural heritage places include sites registered to protect threatened or uncommon species or ecosystems, and significant geological sites to protect their intrinsic features, as identified in the statement of heritage significance.

In addition, there are 31 places nominated for listing. In the past three years, work has been undertaken to reduce the backlog of nominations to the ACT Heritage Register, resulting in the registration of two natural heritage places: Kama Woodland and Hume Paleontological Site. The Kama Woodland site has threatened ecological communities (Box–Gum Woodland and Natural Temperate Grassland) in a setting considered similar to vegetation patterns existing in the area before European settlement. It also contains a high diversity of native species and provides important ecological connectivity.

Table 8.3 Natural heritage places and objects on the ACT Heritage Register, 2011–2015

| Activity | At 30 June 2011 | At 30 June 2012 | At 30 June 2013 | At 30 June 2014 | At 30 June 2015 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Registered places and objects |

6 |

7 |

8 |

8 |

9 |

|

Provisionally registered places and objects |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Nominated places and objects |

37 |

36 |

34 |

31 |

28 |

Source: Data provided by ACT Heritage

Note: To protect restricted information, all areas have been enlarged to block boundary.

Source: Map provided by ACT Heritage

Figure 8.2 Location of natural heritage in the ACT

Aboriginal heritage places and objects

Aboriginal places, objects and tradition are defined within the Heritage Act as follows:2

Aboriginal object means an object associated with Aboriginal people because of Aboriginal tradition.

Aboriginal place means a place associated with Aboriginal people because of Aboriginal tradition.

Tradition is an important part of the history of Aboriginal places and objects, and is defined in the Heritage Act as:2

… the customs, rituals, institutions, beliefs or general way of life of Aboriginal people.

Of the thousands of Aboriginal sites across the ACT, artefact scatters are the most common. They may contain remains from a variety of activities, and include stone artefacts and other materials. There are many other Aboriginal site types in the ACT,20 including:

- scarred trees

- rock art sites

- burials

- grinding grooves

- stone quarries

- ochre quarries

- wooden artefacts

- stone arrangements

- ceremonial places

- post-contact sites.

Why is this indicator important?

All Aboriginal places and objects are protected because of the cultural value they hold for Aboriginal people as part of their history and heritage. Their heritage and archaeological significance for their ability to contribute to our understanding of the Aboriginal history of the ACT, and how this has changed over time, are also protected.

The protection of Aboriginal heritage is important to both Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people of the ACT, because it is a vital part of the story of the region. The protection of Aboriginal heritage allows that heritage to be identified for protection amid growing demands for development across the ACT.

Current monitoring status and interpretation issues

All Aboriginal places and objects in the ACT are protected under the Heritage Act and are recorded in a database, whether or not they are registered. Aboriginal places and objects that have cultural and/or scientific and archaeological value that may meet one or more of the heritage significance criteria under the Heritage Act can be entered onto the ACT Heritage Register.

In some cases, Aboriginal heritage places are protected within urban development areas as part of heritage precincts or other heritage places (see Case study 8.2). Sites are recorded and managed in accordance with conservation management plans endorsed by the ACT Heritage Council.

The whereabouts of Aboriginal artefacts are often unknown because most Aboriginal sites are not mapped. The majority of Aboriginal heritage in the ACT is artefact scatters, which are often uncovered during the development of a site. While development must cease once artefacts are uncovered, in cases where the development cannot continue without damage to the artefacts, they are salvaged and moved elsewhere under consultation with, and with the permission of, Representative Aboriginal Organisations. Some artefacts for research are stored at a depot in Lyneham; other artefacts are returned to country in an area that is not to be disturbed.

For example, around 4000 artefacts, including stone cutting tools, axe heads and grinding stones, were salvaged from the Cotter Dam construction and inundation site during excavation,21 and were sorted into research or return-to-country categories in consultation with the Representative Aboriginal Organisations. The artefacts were returned to country intact and were buried in a location chosen through consultation with Representative Aboriginal Organisations. However, because they are not in the same location where they were found, some members of the Aboriginal community see the heritage as being destroyed or lost. This is because the object and the land are often inextricably linked in Aboriginal culture, and the location of the artefacts is a large part of their value. This is an ongoing issue in the management of Aboriginal heritage in the ACT and elsewhere. The ACT Heritage Council is currently developing an Aboriginal cultural heritage assessment policy to address these issues (ACT Heritage, pers comm, 31 March 2015).

What does this indicator tell us?

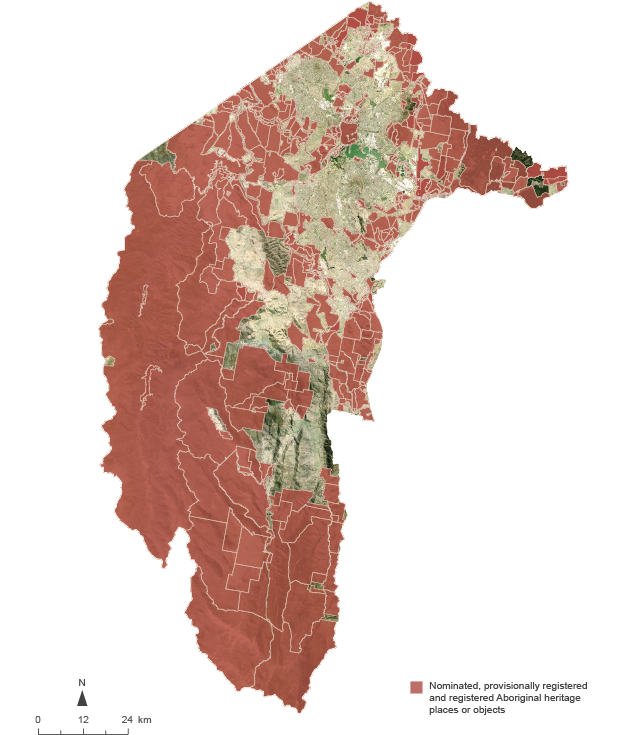

There are currently 72 registrations on the ACT Heritage Register related to Aboriginal heritage places or objects, with a further 4 places or objects nominated (Table 8.4; Figure 8.3). Many of these registrations contain information about more than one Aboriginal place or object. Citations to the register currently include information on 3683 Aboriginal sites, of which 1407 have been recorded as salvaged. Many other sites, ranging from individual artefact scatters to scarred trees, have also been identified and reported to the ACT Heritage Council.

At the end of the 2011 reporting period, there were 67 Aboriginal places and objects registered, with a further 9 nominated for registration. During the reporting period, 6 of the nominated Aboriginal heritage places or objects became registered: the Aboriginal and natural site complex at Horse Park Homestead, an Aboriginal digging stick, the Molonglo Valley Grinding Groove, Onyong’s grave, Birrigai Rock Shelter and Gossan Hill.

Table 8.4 Aboriginal heritage places or objects, 2011–2015

| Activity | At 30 June 2011 | At 30 June 2012 | At 30 June 2013 | At 30 June 2014 | At 30 June 2015 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Registered places and objects |

67 |

68 |

69 |

69 |

72 |

|

Provisionally registered places and objects |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Nominated places and objects |

9 |

8 |

7 |

7 |

4 |

Source: Data provided by ACT Heritage

Aboriginal rock art at Yankee Hat, Namadgi National ParkPhoto: ACT Government

Note: To protect restricted information, all areas have been enlarged to block boundary.

Source: Map provided by ACT Heritage

Figure 8.3 Location of Aboriginal heritage in the ACT

Assessment summaries

for indicators of heritage state and trends

| Indicator | Reasoning | Assessment grade | Confidence | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Very poor | Poor | Fair | Good | Very good | In state grade | In trend grade | ||

| Number of historic heritage places | 414 historic places and objects are registered on the ACT Heritage Register, which has grown by 63 since 2011. The number of nominations has decreased, due to an audit that removed duplication and ineligible nominations on National Land There is reasonable confidence in the state and trend of this indicator – the processes for identifying and protecting historic heritage places were sound, although at times constrained by limited resources |

Stable | Limited evidence or limited consensus | Limited evidence or limited consensus | ||||

| Number of natural heritage places | Nine natural heritage places or objects are registered on the ACT Heritage Register, compared with six by the end of the previous reporting period (comments above for historic heritage apply here also). Although the number is low, the geographic coverage of these areas is relatively large. Two new sites, Kama Woodland and Hume Paleontological Site, have been added. There are a further 31 nominations |

Stable | Limited evidence or limited consensus | Limited evidence or limited consensus | ||||

| Number of Aboriginal heritage places | All Aboriginal heritage places and objects in the ACT are protected under the Heritage Act 2004, regardless of whether they are listed on the ACT Heritage Register. These are expected to number around 3000 sites. There are currently 72 registrations on the ACT Heritage Register related to Aboriginal heritage places or objects, an increase of 5 since 2010–11, with a further 4 places or objects nominated Some members of the Aboriginal community have concerns that salvaging and rehoming of Aboriginal heritage objects found during development may damage the value of the objects, as they are often inextricably linked to the land |

Improving | Limited evidence or limited consensus | Limited evidence or limited consensus | ||||

Recent trends

Confidence

Case study 8.2 Canberra Tracks

What are Canberra Tracks?

Canberra Tracks are a network of self-drive tracks to many of Canberra’s important historic sites. The eight tracks take in aspects of historic, Aboriginal and natural heritage. These include the Ngunnawal Country Track, which traverses some of the Aboriginal history of the Canberra area; the Limestone Plains Track, which looks at the exploration and colonisation of the area by Europeans; and the Belconnen Heritage Track, which tells the story of Belconnen over the years, from Aboriginal uses to recent development.22

Why are Canberra Tracks important?

Canberra Tracks provide an alternative way of learning about Canberra’s history, and allow residents and tourists to explore areas of the city that interest them and to find out about the heritage of their local area.

How can the community use the tracks?

There are several ways the community can experience Canberra Tracks. The Canberra Tracks websitea has information about each of the tracks, including maps and pointers on what to look out for along the way.

Each track includes interpretive signage telling stories of our heritage from pre-European settlement to the recent past.23 Also available while you are on the tracks, the Canberra Tracks mobile phone app, developed in conjunction with students from the University of Canberra, provides video, audio and images to enhance the stories you encounter along the way.24

Canberra Tracks are signposted across the city. Photo: ACT Government

8.3.2 Pressures

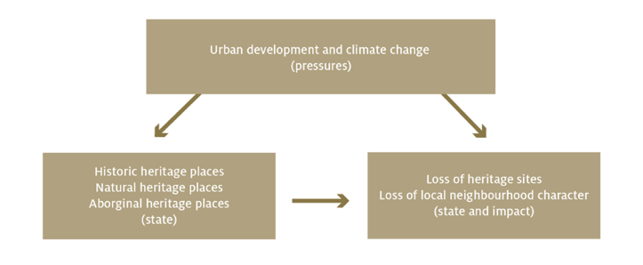

The major pressures on heritage places and objects in the ACT are changes to land use – in particular, urban development. This includes both greenfield development (use of previously undeveloped land) and urban infill (use of land within a built-up area for further construction). The changing climate is also likely to be an added pressure on some heritage places and objects.

Pressures can affect the condition of our heritage and can also cause the loss of heritage sites, either directly or through degradation of the place or object (Figure 8.4).

Figure 8.4 Effects of pressures on heritage

Climate change

As described in Chapter 2: Climate, likely changes to the climate of the ACT and region include higher average temperatures, changed rainfall patterns, and an increase in severe weather events and high fire danger.

There is little known about the actual impacts that climate change may have on heritage places in the ACT and elsewhere. Although ongoing monitoring of the condition of sites may provide an insight into future climate-related impacts, it is likely to be difficult to determine which impacts are the direct result of climate change.

Changes to temperature and rainfall patterns may quicken the deterioration of surfaces and building fabrics, and lead to lifestyle changes, which in themselves can affect historic heritage values. The expected increased frequency of severe weather events may alter ecosystems and cause direct damage to natural and cultural heritage.25 Natural heritage places listed for the protection of rare or endangered species, such as the two sites in the ACT containing large populations of the endangered Button Wrinklewort, may be under threat if changes in climatic conditions threaten the survival of the species.

Fire is always a potential risk factor for heritage in the ACT and may be an even more prevalent risk with climate change. Fire is a particular risk for historic heritage buildings and precincts, because fire can irreparably damage such sites. Fire is also a risk factor for Aboriginal heritage sites and historic sites in rural areas. For example, a number of rock art sites, the Mount Stromlo Observatory and a large number of the surveyors’ blazed trees marking the boundary of the ACT and New South Wales were destroyed in the 2003 bushfires in the ACT.

Land use and development

Why is this indicator important?

A key pressure on heritage in the ACT is the ongoing demand for urban development.

Both greenfield development and urban infill can affect heritage sites and objects. Greenfield developments particularly affect Aboriginal and natural heritage sites and objects, as these may be disturbed during site preparation and construction. As previously discussed, the salvaging and rehoming of Aboriginal heritage objects found during development may damage the value of the objects, as they are often inextricably linked to the land.

Historic heritage is most heavily affected by urban infill and redevelopment, particularly buildings within heritage precincts. Although homes in the Garden City precincts are prized for the same assets that see them protected, they are also subject to the pressures of changing lifestyles that lead to redevelopment and refurbishment.14

In some cases, houses will retain only the front wall or facade of the building and refurbish the interior. Although this may retain the values for which the place is registered, there is some argument that heritage is still lost through this process. In other cases, part of the heritage value of sites is the amount of land available for planting of gardens. Actions such as extension of houses or addition of pools that take up more of the site may diminish the heritage values.

Current monitoring status and interpretation issues

ACT Heritage has developed policies and guidelines to guide development and alterations affecting heritage buildings or precincts.

If a development may affect a heritage site or object, advice from the ACT Heritage Council is required as part of the development application (DA) process. The ACT Planning and Land Authority will automatically forward any DAs that may affect heritage places or objects to the council for advice.

In the case of development in or around heritage-listed buildings, usually only developments resulting in changes to the facade will require approval under the Heritage Act. However, sometimes internal features of buildings may also warrant protection. Works usually exempt from approvals under the Planning and Development Act 2007 may require approval if they occur on heritage buildings, including, for example, the installation of solar panels and pergolas.

Monitoring the number of requests for heritage advice on DAs allows us to keep track of how much and what types of development may affect heritage sites.

What does this indicator tell us?

The total number of DAs affected by heritage issues has increased since 2011 (Table 8.5). On average, 180 DAs relating to registered heritage places have been processed each year.

Table 8.5 Development applications related to heritage, 2010–2015

| Activity | 2010–11 | 2011–12 | 2012–13 | 2013–14 | 2014–15 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Advice on development referrals – heritage |

94 |

190 |

169 |

220 |

228 |

|

Advice on development applications (ACT Planning and Land Authority) – heritage |

65 |

182 |

153 |

167 |

139 |

|

ACT Planning and Land Authority development applications – heritage (%) |

5 |

16 |

13 |

15 |

11 |

|

Development applications (ACT Planning and Land Authority) – total |

1293 |

1136 |

1207 |

1104 |

1218 |

|

Minor works applications |

29 |

8 |

16 |

47 |

49 |

|

National Capital Authority works applications – heritage |

NA |

NA |

NA |

6 |

31 |

NA = data not available

Source: Data provided by ACT Heritage

DAs may be referred to the ACT Heritage Council for advice, as part of the ACT Planning and Land Authority’s approval process. The ACT Heritage Council will assess whether or not a development may detrimentally impact on the heritage values of a place or object. Such assessment may conclude that an impact is likely unless certain conditions are applied to the development.

In 2011–2015, most (60%) DAs referred to the ACT Heritage Council were not objected to, or DAs (26.5%) were not objected to based on specific heritage conditions (Table 8.6). Of the applications where additional information was requested, most were not objected to after the provision of the additional information. The council provided advice objecting or requiring changes to 11% of the DAs received during 2011–2015.

Table 8.6 Development applications amended, subject to conditions or refused due to heritage constraints, 2010–2015

| Activity | 2010–11 | 2011–12 | 2012–13 | 2013–14 | 2014–15 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Development applications – heritage |

94 |

190 |

169 |

220 |

228 |

|

Applications with no objections |

48 (51%) |

117 (62%) |

87 (52%) |

138 (62%) |

148 (65%) |

|

Applications with no objections subject to conditions |

21 (23%) |

48 (25%) |

66 (39%) |

61 (28%) |

32 (14%) |

|

Applications with additional information requested |

4 (4%) |

10 (6%) |

2 (1%) |

4 (2%) |

17 (7%) |

|

Objections to approval |

21 (22%) |

15 (7%) |

14 (8%) |

17 (8%) |

31 (14%) |

Source: Data provided by ACT Heritage

Assessment summaries

for indicators of heritage pressures

| Indicator | Reasoning | Assessment grade | Confidence | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Very low | Low | Moderate | High | Very high | In state grade | In trend grade | ||

| Land use and development | Total number of development applications (DAs) increased marginally since 2010–11. The percentage of all DAs relevant to heritage issues decreased since 2010–11. Although this indicates a small increase in development pressure, these applications must be referred to the ACT Heritage Council, which can recommend the best protection for heritage through application approvals, conditional approvals, modifications or refusals. Both greenfield development and urban infill can affect heritage sites and objects. Greenfield developments particularly affect Aboriginal and natural heritage sites. As previously discussed, the salvaging and rehoming of Aboriginal heritage objects found during development may damage the value of the objects, as they are often inextricably linked to the land. Historic heritage is most heavily affected by urban infill and redevelopment, particularly buildings within heritage precincts. This indicator provides reasonable confidence in the level of development pressure on heritage matters |

Improving | Limited evidence or limited consensus | Limited evidence or limited consensus | ||||

Recent trends

Confidence

Resilience to pressures

A resilience assessment involves looking at the systems, networks, human resources and feedback loops involved in maintaining environmental values (see Chapter 9).

In the ACT, heritage values are well articulated and codified in processes through which sites can be declared as having heritage value. The Heritage Act embeds leading approaches to heritage protection, with clear and transparent processes for assessing heritage value and identifying where intervention may be needed before development occurs. This enables rapid communication about whether there might be concerns about changes to heritage values. The concept of thresholds, relating to the integrity of the site, has been adopted in deciding when heritage sites qualify for registration. In addition, all Aboriginal sites must automatically be notified to the ACT Government, a more direct and immediate protection mechanism than in some other jurisdictions. However, it should be noted that there is ongoing societal debate in the ACT about what constitutes heritage value, reflecting often rapidly evolving societal values.

The services that heritage places or objects provide to the community are key to their relevance and therefore their resilience. In some cases, the resilience of the ACT’s heritage is bolstered by the adaptive reuse of heritage places. For example, the re-imagining of the heritage-listed former Kingston Powerhouse as Canberra Glassworks has prolonged the use and care of the site, and given it a new identity and importance within the community. Canberra Glassworks has been constructed within the existing fabric of the Kingston Powerhouse, preserving the heritage values, including many of the original finishes and fittings, and providing interpretive signage to inform visitors of the history of the place.26

Threats to heritage are well understood, such as new development, loss of value, lack of maintenance and lack of recognition of heritage values. There are requirements to address some threatening processes – for example, through requirements to identify heritage values when development occurs. However, threats in the form of lack of maintenance, decay or loss of heritage value due to incremental processes are less readily able to be addressed. A key challenge to maintaining heritage values is adequate resourcing of longer-term threats to heritage, such as maintenance of heritage sites. In addition, monitoring relies on community feedback, rather than more systemic heritage assessment processes.

There are strong networks to manage heritage values in the ACT, with investment in public education about heritage, strong linkages to research in this area, and clear processes by which ACT residents can become involved in heritage-related discussions. Heritage assessment processes access a wide range of viewpoints, and stakeholders are strongly engaged in developing guidelines, setting criteria and making assessments. Stakeholders are able to access a transparent system for listing heritage assets, and are readily able to discuss heritage concerns and values. However, short-term resourcing and, in some cases, a lack of resourcing can reduce effectiveness of these networks.