This chapter provides an assessment of the state of biodiversity in the Australian Capital Territory (ACT), including trends in the extent, abundance and condition of biodiversity. The chapter also examines the major pressures directly affecting biodiversity, such as land clearance, feral animals and weeds.

This chapter will:

- define biodiversity

- explain why biodiversity is important

- explain how biodiversity is measured in the ACT

- describe the current state of biodiversity in the ACT

- assess whether biodiversity is stable, improving or declining

- describe the pressures on the ACT’s biodiversity and the impacts these pressures are having

- assess whether these impacts are stable, increasing or decreasing

- describe the legal framework that protects biodiversity in the ACT

- summarise government biodiversity management responses.

7.2.1 What is biodiversity?

Biodiversity can be described in many different ways.1 In fact, the scientific literature contains almost 100 different definitions.1 Put simply, biodiversity is the variety of life on Earth. This can include the diversity of genes within a species, the diversity of species within a landscape and the diversity of ecosystems across landscapes. It can also include the diversity of ecological processes, such as seed dispersal, pollination and nutrient cycling, that underpin the functioning of ecosystems.

All these levels of biodiversity work together to create the complexity of life on Earth.

Genetic diversity

Genetic diversity is the variety of genes within a species. Each species is made up of individuals that have their own particular genetic composition.

Species diversity

Species diversity is the variety of species within a habitat or a region. Some habitats, such as rainforests and coral reefs, have many species. Others, such as salt flats or a polluted stream, have fewer. In Australia, more than 80% of plant and animal species are endemic, which means that they occur naturally only in Australia. In Australia, it is not just the individual species that are endemic – whole families of animals and plants are endemic. Seven families of mammals, 4 of birds and 12 of flowering plants are endemic to Australia. The ACT has six endemic plant species including the Canberra Spider Orchid, Brindabella Midge Orchid, Ginninderra Peppercress, Tuggeranong Lignum, Murrumbidgee Bossiaea and the Black Mountain Leopard Orchid.

Ecosystem diversity

Ecosystem diversity is the variety of ecosystems in a given area. An ecosystem is a suite of organisms and their physical environment interacting together. An ecosystem can cover a large area, such as a whole forest or the Great Barrier Reef, or a small area, such as a pond or the back of a Spider Crab’s shell that provides a home for sponges, algae and worms. In the ACT, large ecosystems include areas of Box–Gum Woodland and Natural Temperate Grassland, and microecosystems are found in and on tiny pockets of soil that contain unique combinations of plants, insects and microbes.

Ecosystem processes and functions

Ecological processes, such as seed dispersal, pollination, the decomposition of waste, and nutrient and water cycling, underpin how well ecosystems function.2

Biodiversity in Australia

‘Megadiverse’ describes countries or areas with very high levels of biodiversity. It is estimated that there are 13.6 million species of plants, animals and microorganisms on Earth. As a megadiverse country, Australia has about one million of these, which represents more than 7% of the world’s total and more than twice the number of species in Europe and North America combined. Twelve megadiverse countries, including Australia, contain about 75% of Earth’s total biodiversity.3

Australia has more species of:4

- vascular plants (than 94% of other countries)

- nonfish vertebrate animals (mammals, birds, reptiles and amphibians) (95%)

- mammals (93%)

- birds (79%)

- amphibians (95%)

- reptiles (than any other country on Earth).

It has been conservatively estimated that invertebrates comprise more than 80% of the world’s biodiversity, in terms of both the number of species and biomass. In Australia, there are estimates of as many as 300 000 species of nonmarine invertebrates, of which less than 100 000 have been described. (In comparison, Australia is home to approximately 16 000 species of higher plants and 5000 species of vertebrates.5) For example, Australian ants are highly diverse compared with elsewhere in the world, with an estimated 4000 species. The 452-hectare (ha) Black Mountain Nature Reserve in Canberra alone has more species of ant than the whole of Britain (more than 100 species, compared with around 41 species in Britain).6

Biodiversity in the ACT

The Atlas of Living Australia (ALA) records 2316 animal species and 4322 plant species within a 10-kilometre radius of Civic: 45 mammals, 420 birds, 39 reptiles, 17 amphibians, 5 fish, 15 molluscs, 1770 arthropods, 5 crustaceans and 1683 insects. In early 2015, there were 1.92 million records of species that have been observed or found in the ACT, according to the ALA. The species recorded are mammals, birds, insects, amphibians, reptiles, fish, molluscs, crustaceans, plants and fungi.7

Two species recorded in the ALA represent the bird and floral emblems of the ACT: the Gang-Gang Cockatoo and the Royal Bluebell. (The ACT does not have a mammal emblem.)

The 2012 Census of the vascular plants, hornworts, liverworts and slime moulds of the Australian Capital Territory found 1752 native species (1645 vascular plants, 3 hornworts, 77 liverworts and 27 slime moulds). It also found 556 species introduced from overseas and 42 species introduced from elsewhere in Australia.8

7.2.2 Why is biodiversity important?

Biodiversity provides specific benefits to humans and to ecosystems. Although some of these benefits can be measured and quantified, biodiversity also has intrinsic value. That is, many people value biodiversity for its own sake and regard its worth as unquantifiable.9

Humans and biodiversity

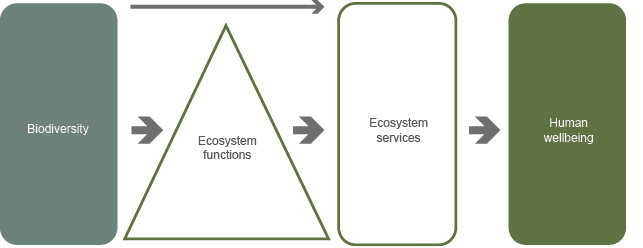

Biodiversity is fundamental to human life. The complex and dynamic interactions between plants, animals and microorganisms underpin ecosystem functions and services, and deliver a range of benefits to human wellbeing (Figure 7.1).

Figure 7.1 Biodiversity contributes directly and indirectly to human wellbeing

Biodiversity contributes to human wellbeing directly and indirectly. Some of the direct benefits of biodiversity include the variety of foods, fibres, medicines and other natural products that support our lives. A diet that includes a diverse range of foods is important to the maintenance of human health, and can protect against disease and poor nutritional status. Biodiverse environments, including in urban green spaces, have also been associated with increased mental wellbeing.10

Many economically valuable industries are based on biodiversity, relying on particular species or using biodiverse products. For instance, in recent years, it has been estimated that, each year, Australia’s commercial fisheries are worth $2.2 billion, kangaroo harvesting $245 million, bush-food production $100 million and wildflower exports $30 million. Nature-based tourism is also a significant industry in Australia.11

The indirect contributions of biodiversity to human wellbeing are also enormously important. Biodiversity forms a core component of ecosystems; it enables many ecosystem functions and plays a pivotal role in processes that support the provision of the direct benefits considered previously. For example:12

- climate regulation keeps temperature at ranges suitable for humans and provides rainfall for water supplies

- water purification provides clean water

- nutrient cycling supports plant growth and food production

- pollination drives crop production

- carbon sequestration and breakdown of chemicals in soils take care of many byproducts of human societies

- pest control can support the production of foods.

In agricultural ecosystems, genetic diversity allows farmers and plant breeders to improve plant productivity, increase the capacity of crops to cope with weather variability, and help manage pests and diseases.13

There may be many more ways that humans benefit from biodiversity that we are yet to understand or that have not been explored, such as the contribution of particular wild plant species to medical science. Conserving biodiversity is therefore seen as crucial to maintain people’s future ‘option values’.14

Ecosystems and resilience

Many scientists consider that biodiversity plays an ‘insurance’ role in ecosystems – making species and ecosystems more resilient to shocks and pressures. A diversity of species, ecosystems and ecological processes can help ecosystems to maintain their core functions in the face of environmental change. The loss of species or changes in the species mix may reduce the capacity of ecosystems to support current biodiversity and ecosystem services.9

Genetic diversity plays an important role in the survival and adaptability of a species. When a population of an organism contains a large gene pool – that is, the genetic composition of individuals in the population varies significantly – the group has a greater chance of surviving and flourishing than a population with limited genetic variability. Genetic diversity also reduces the incidence of unfavourable inherited traits. To conserve genetic diversity, different populations of a species must be conserved.

7.2.3 How do we measure biodiversity?

Estimates of the total number of species in the world vary from 5 million to more than 50 million. For Australia there are 147 579 accepted described species, but the estimate of the number of species overall is over 560 000.15 Australian figures for flowering plants have varied from 15 638 in the early 2000s to 18 821 in 2006. The total number of native Australian flowering plant species would now appear to be somewhere between 20 000 and 21 000, or possibly slightly higher.15

The fact that only a small proportion of total species are known, let alone counted, means that it is not possible to measure overall biodiversity. In addition, biodiversity can be quantified at many levels of biological organisation – from the molecular to the ecosystem – and, again, it is not possible to measure absolute biodiversity at all of these levels (Scientific Committee State of the Environment Report reviewer, pers comm by email, 1 October 2015).

There are, however, methods to measure components of biodiversity that serve as indicators of how it might be changing. The choice of measure should be dictated by the information needed to inform particular environmental management strategies, or to evaluate whether environmental management strategies are working.

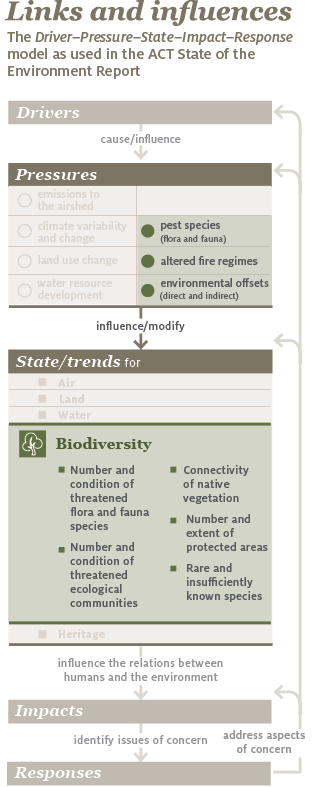

Historically, State of the Environment Reports have used consistent biodiversity measures so that trends in biodiversity can be reported on. The reports have also aimed to review and improve indicators. For this 2011–2015 report, three additional indicators have been added to reflect the current use of biodiversity offsets and increased knowledge about uncommon plant species. This report examines:

- state and trends

- extent and abundance of threatened flora and fauna species

- extent and condition of threatened ecological communities

- connectivity of threatened terrestrial native vegetation

- extent and health of protected areas

- rare and insufficiently known species and ecological communities

- impacts and pressures

- extent and abundance of pest species

- altered fire regimes

- direct and indirect environmental offsets.

It should be noted that complete data are not available for these indicators. In addition, some important issues are not measured because of data limitations or scientific uncertainty, or a lack of robust measurement techniques.

a Some circumspection is required in relation to ALA data. Data can include specimens housed within the area of request, but actually collected elsewhere. ALA data also include historical records, and some of these species may now be locally extinct, or the precision of describing the original location is such that the collection may have occurred outside the ACT (State of the Environment Report reviewer, pers comm, 30 September 2015).

b http://biocache.ala.org.au/explore/your-area#-35.29644439338361|

149.13557315699757|11|ALL_SPECIES, accessed 14 July 2015

c Previous ACT State of the Environment Reports are available at http://www.environmentcommissioner.act.gov.au/publications/soe_about-the-report/soe_archive.

d Previous State of the Environment Reports and State of the Environment Report reviews are available at http://www.environmentcommissioner.act.gov.au/publications/soe.