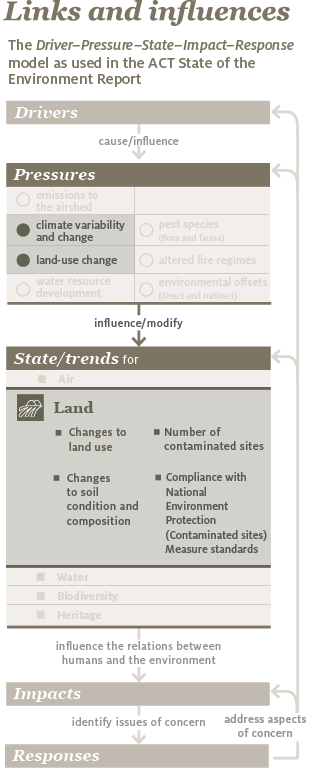

This chapter reports against indicators that measure the state of land use and soil condition, and examines the existing and future pressures on Australian Capital Territory (ACT) land.

This chapter will:

- define land

- explain why land is important

- explain how land is measured in the ACT

- describe the current state of land in the ACT

- assess whether land values in the ACT are stable, improving or declining

- describe the pressures on the ACT’s land and the impacts these pressures are having

- assess whether these impacts are stable, increasing or decreasing

- summarise government land management responses.

5.2.1 What is land?

Land can be described and classified in many ways, depending on whether the focus is on the underlying geology, landforms, soils, ecological communities, sociocultural boundaries, associated industries or other features.

In the context of this State of the Environment Report, land is categorised in relation to its:

- physical composition (ie geomorphology and, specifically, soil)

- jurisdictional boundaries and uses

- effect upon the other themes – air, water, heritage and biodiversity – that are assessed in this report.

5.2.2 Why is land important?

Human wellbeing is dependent on land. The interactions of soil, air, water, plants, animals and natural processes provide a diverse range of services, including food and clean water production, nutrient recycling, erosion control and recreation opportunities. How land is used and managed can significantly affect its capacity to provide these services, which in turn can have direct and indirect impacts on human wellbeing.

Soil is a fundamental part of ecosystems and natural processes. Soil provides a growing medium for plants, which people and livestock rely on. In urban environments, soil provides the medium for ornamental gardens, urban food production and green spaces that support a range of amenity values.1,2 This living infrastructure adds to the livability of our urban areas, and is conducive to physical activity and mental wellbeing (see Chapter 9). Indirectly, humans benefit from the many roles of soil, which include buffering and moderating the movement of water through ecosystems; disposing of wastes and dead organic matter; renewing fertility; regulating major element cycles such as carbon, nitrogen and sulfur; and ameliorating urban heat effects.1,3,4

Land – and the social, economic and ecological values it provides – is fundamental to the identity and purpose of the ACT. Land use and land-use change, and soil condition are important topics to explore when examining how land contributes to human wellbeing through the delivery of ecosystem services, and also how human activities affect these. A resilience approach can help to secure the benefits that land provides, despite ongoing pressures from a range of sources, including climate change, vegetation clearing and urban expansion.

Community case study 5.1 highlights the importance of public green space and gardens.

Erosion from a building site at MolongloPhoto: TAMS, ACT Government

Community case study 5.1

Community gardens in the ACT

A variety of fruit and vegetables is grown at the Community Garden in Charnwood. Photo: ACT Government for both images

Community gardens in the Australian Capital Territory (ACT) are mostly located on public land, and give members a place to grow their own fruit and vegetables, and exchange gardening ideas and experiences. Organic methods – which can help improve soils – are encouraged and supported. Social benefits include increased access to fresh food, community learning, and a sense of belonging and pride in the community. These gardens also offer productive ways to use land that would be otherwise at risk of weed invasion, erosion and other degradation. The added vegetation also creates habitat values in the urban environment.

A review of community gardens undertaken in 2012, by what is now the Environment and Planning Directorate, reported a growing demand for community gardens in the ACT. It also highlighted positive social, cultural, health, economic and educational outcomes for participants – and the community more broadly – in addition to environmental and ecological benefits.

The review identified that at least 77 food-producing school gardening sites existed in the ACT, in addition to 17 community gardens. The latter mainly comprised fenced, individual plots, and organic or low-chemical cultivation methods. The variety of designs, intentions and governance/management arrangements in place indicated that there is no single ‘right’ model for a community garden.

The study found that effective cross-sectoral partnerships and access to information are integral to the success of these enterprises. Succession planning for managers/volunteers and having community gardens within walking distance of people’s place of residence were also identified as key issues for success. In 2015–16, the Environment and Planning Directorate made $25 000 available for individual small grants of up to $5000 for new or existing community gardens aimed at achieving a range of social outcomes. Ongoing funding is yet to be confirmed.

The Canberra Organic Growers Society (COGS), a not-for-profit organisation that encourages and supports organic gardening methods, is licensed by the ACT Government to operate 12 community gardens on government land in the ACT. The COGS garden at Holder has been in operation since 2001, and has a very active gardening community and about 57 plots of varying sizes. Casuarinas were planted to provide wind protection and shade for a communal orchard, herb garden, grapevines, raspberries and a vegetable patch. The garden also has a greenhouse, shed, barbecue, compost heaps and tools. Gardeners share the allotment with a range of passing native and non-native wildlife.

A group of Lyneham residents has started a slightly different venture in urban food production. Working with Territory and Municipal Services, they are setting up a shared food forest. The site is on a small piece of low-use public land behind the Lyneham Primary School, adjacent to Sullivans Creek stormwater drain and a short walk from the Lyneham shops. The first stage of works for the food forest, known as Lyneham Commons, will involve soil preparation and planting a variety of fruit trees. Approximately 30 fruit and nut trees and complementary plants, selected for resistance to pests and disease and to suit local conditions, will be planted during the next couple of years.

Sources:

a http://www.ecoaction.com.au/resources/community/edible-plants

b http://www.planning.act.gov.au/tools_resources/research-based-planning/demand_for_community_gardens_and_their_benefits

c http://www.environment.act.gov.au/cpr/grants/act_environment_grants

d http://www.cogs.asn.au/community-gardense

e http://www.cogs.asn.au/community-gardens/holder-garden

f http://timetotalk.act.gov.au/consultations/?engagement=lyneham-food-forest

5.2.3 How do we measure land condition?

An established set of indicators is used to measure land condition:

- state and trend

- land use

- soil condition (soil type and soil properties)

- contaminated sites

- compliance with the National Environment Protection (Assessment of Site Contamination) Measure (Assessment of Site Contamination NEPM)

- impacts and pressures

- land-use change (number and type of development applications, and greenfield versus infill development).

View of the Molonglo development front from Mount Stromlo

Photo: Office of the Commissioner for Sustainability and the Environment