7.3.1 State and trends

Threatened flora and fauna species

Why is this indicator important?

The extent and abundance of threatened flora and fauna species provide a measure of biodiversity. In addition, movement in statutory species listings – for example, if a species moves from vulnerable to endangered – raises concerns about potential biodiversity loss (although the listing process is also influenced by other factors, such as effort and attention given to different species by government, researchers and interest groups). Population changes are also one of the best indirect measures currently available for assessing the effectiveness of management actions.

Current monitoring status and interpretation issues

The flora and fauna species described in this indicator are all prescribed as threatened under s. 63 of the Nature Conservation Act 2014. To be eligible for inclusion on the list, the status of the species must comply with prescribed criteria and be one of:

- extinct

- extinct in the wild

- critically endangered

- endangered

- vulnerable

- conservation dependent

- provisional.

Threatened species in the ACT are currently listed as either endangered or vulnerable. Species that may be threatened for which we have little information are addressed under the indicator ‘Rare and insufficiently known species and ecological communities’. See also ‘Current monitoring and interpretation issues’ in ‘Rare and insufficiently known species and ecological communities’ for information on new statutory categories for rare and data-deficient species.

The species currently prescribed as threatened under the Nature Conservation Act are:

- endangered species

- Brush-Tailed Rock-Wallaby (Petrogale penicillata)

- Smoky Mouse (Pseudomys fumeus)

- Regent Honeyeater (Xanthomyza phrygia)

- Grassland Earless Dragon (Tympanocryptis pinguicolla)

- Northern Corroboree Frog (Pseudophryne pengilleyi)

- Macquarie Perch (Macquaria australasica)

- Silver Perch (Bidyanus bidyanus)

- Trout Cod (Maccullochella macquariensis)

- Golden Sun Moth (Synemon plana)

- Baeuerlen’s Gentian (Gentiana baeuerlenii)

- Brindabella Midge Orchid (Corunastylis ectopa)

- Button Wrinklewort (Rutidosis leptorrhynchoides)

- Canberra Spider Orchid (Arachnorchis actensis)

- Ginninderra Peppercress (Lepidium ginninderrense)

- Murrumbidgee Bossiaea (Bossiaea grayi)

- Small Purple Pea (Swainsona recta)

- Tarengo Leek Orchid (Prasophyllum petilum)

- Tuggeranong Lignum (Muehlenbeckia tuggeranong)

- vulnerable species

- Spotted-Tailed Quoll (Dasyurus maculatus)

- Brown Treecreeper (Climacteris picumnus)

- Glossy Black Cockatoo (Calyptorhynchus lathami)

- Hooded Robin (Melanodryas cucullata)

- Little Eagle (Hieraaetus morphnoides)

- Painted Honeyeater (Grantiella picta)

- Scarlet Robin (Petroica multicolor)

- Superb Parrot (Polytelis swainsonii)

- Swift Parrot (Lathamus discolor)

- Varied Sitella (Daphoenositta chrysoptera)

- White-Winged Triller (Lalage sueurii)

- Pink-Tailed Worm Lizard (Aprasia parapulchella)

- Striped Legless Lizard (Delma impar)

- Murray River Crayfish (Euastacus armatus)

- Two-Spined Blackfish (Gadopsis bispinosus)

- Perunga Grasshopper (Perunga ochracea).

This indicator reports on the state and trend of the extent and, where possible, the abundance of each listed threatened species. The quality and quantity of the reporting are commensurate with the monitoring data available in the reporting period.

What does this indicator tell us?

Vulnerable species

A native species is eligible to be included in the vulnerable category on the threatened native species list if it is not critically endangered or endangered, but is facing a high risk of extinction in the wild in the medium-term future.

Spotted-Tailed Quoll

Spotted-Tailed Quoll sightings in the ACT are mainly unplanned, especially in the Gudgenby area of Namadgi National Park, and those that have met with misadventure (eg killed on roads or driven up backyard trees by dogs). Two individuals were seen living in unsuitable urban habitat (eg roadside drains). No deliberate survey has ever detected the species in the ACT, although scats were found at Gudgenby during a search for quoll latrines in 2005.

In 2013, using an improved survey method, the Gudgenby Catchment was surveyed down to Glendale Crossing. The survey provided no evidence of quolls.16 Fox scats were found on the quoll latrine sites identified in previous years and were common elsewhere in the area.

Brown Treecreeper

In 2014, the Canberra Ornithologists Group (COG) recorded 64 sightings of Brown Treecreeper, a 30% drop from 2013.17 This is the second drop in annual records after a very gradual rise from 20 in 1998 to 138 in 2012. One breeding pair was recorded in 2014, well down on 11 records in 1989 and 10 in 2011.17 Brown Treecreepers are possibly in decline (Scientific Committee State of the Environment Report reviewer, pers comm by email, 1 October 2015).

Glossy Black Cockatoo

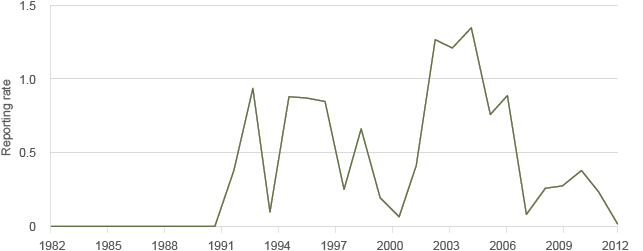

The Glossy Black Cockatoo is an uncommon visitor to the ACT. The species is occasionally seen in Casuarina trees (used as a food source) on Mounts Ainslie and Majura. Cockatoo sightings, as reported by COG, have declined from a peak in 2003–2005 (Figure 7.2); however, the Scientific Committee states that Glossy Black Cockatoos show no long-term declining trend.18

Source: Canberra Ornithologists Group, http://canberrabirds.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/Glossy-Black-Cockatoo.pdf

Figure 7.2 Percentage of datasheets reporting Glossy Black Cockatoo, 1981–2013

Conservation and Planning Research (CPR) reports that the Glossy Black Cockatoo has recently been found to breed on Mount Majura.

Hooded Robin

In 2014, Hooded Robin recorded sightings were 50% higher than in 2013, which was the lowest since 1985. Until 2014, there was a steady decline since the high numbers of sightings in 2009. The majority of sightings were in summer (46%). This is different to the long-term seasonal distribution, which is fairly even across the seasons, and different to the previous year, when the majority of records were in autumn. One breeding pair was recorded in 2014.19

The majority of known Hooded Robin habitat is protected in conservation areas (Mulligans Flat, Goorooyarroo, Namadgi, Jarramlee), but habitat also occurs on land managed by the Australian Government Department of Defence (Majura Army Firing Area), and in the Naas and Murrumbidgee valleys. The population in Mulligans Flat appears to have recently become extinct.20

Little Eagle

Each year, many sightings are recorded of nonbreeding Little Eagles, which could tend to obscure the true status of the species in the ACT. Only three breeding pairs of Little Eagles are known, all in peri-urban areas. Retaining this species in the ACT (ie as a breeding population) is a challenge. Although nonbreeding individuals visit the upland parts of the ACT and the Murrumbidgee River Corridor, the breeding habitat corresponds to areas planned for urban development. The foraging and territorial area required by a pair of Little Eagles is unknown, but it appears to be so large that no existing urban reserve could meet the needs of a pair. The first tracking studies of the species are planned for 2015–2017 in areas proposed for development. The project will seek ways to accommodate the apparently competing goals of retaining the species and accommodating urban expansion.

In addition, there is a working theory that rabbits (which form the main contemporary diet of the Little Eagle) baited with pindone may disable or be fatal to the Little Eagle. Retaining foraging habitat without this control may be important to the survival of this species.21

Painted Honeyeater

The Painted Honeyeater is a rare visitor to the ACT. There was a significant increase in Painted Honeyeater numbers observed in the ACT in the early 2000s.22,23 Numbers appear to have declined since then.23

Scarlet Robin

There has been a significant long-term decline in Scarlet Robin occupancy rates in the ACT since 1999.24 In 2015, the ACT Scientific Committee identified the Scarlet Robin as vulnerable, meaning that the species is at risk of premature extinction in the ACT region in the next 25–50 years.25

Superb Parrot

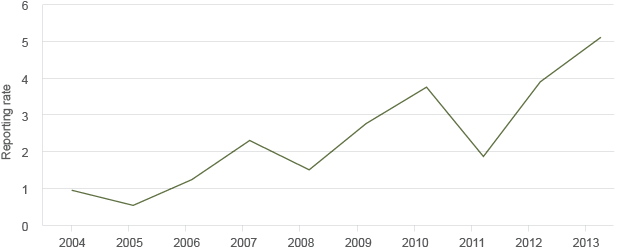

Until the summer of 2005–06, the Superb Parrot was known as a rare visitor to the ACT. Since then, small flocks have been regularly observed feeding on ovals and street trees in Belconnen and parts of Gungahlin from September to March (Figure 7.3). Numbers appeared to decrease in 2011–12, but the reason for this is unknown and the recording is thought to be an outlier.

Source: Canberra Ornithologists Group28

Figure 7.3 Superb Parrot reporting rates

Targeted surveys have located three areas in which breeding is concentrated, with 15–20 pairs of breeding birds nesting at each of the Throsby Ridge and Central Molonglo sites, and a further location confirmed in 2014 at Spring Valley Farm south of the Molonglo River.26 The occasional pair also nests within Mulligans Flat and Goorooyarroo nature reserves. Birds may also be breeding south of the Molonglo River in the Pine Ridge area, but this has to be confirmed. In 2013, Superb Parrots appeared to overwinter in Canberra for the first time (S Henderson, COG, pers comm, 1 August 2013).

However, it should be noted that retired Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) scientist and long-serving COG member Chris Davey indicated that seeing more birds does not necessarily mean an increase in numbers. It may indicate that their distribution has changed because of climate change or other factors.27

Swift Parrot

The Swift Parrot is an occasional nonbreeding winter migrant to the ACT from Tasmania. It has been recorded in eucalypt forest and woodland, mainly in the Majura–Mount Ainslie area. There were nine recorded sightings in 2013–14.29

Varied Sittella

Sightings of Varied Sittella were relatively consistent for 2013 and 2014, although well below both the 10- and 30-year averages. Records of breeding pairs have been consistently between five and seven for the past three years.30

White-Winged Triller

The White-Winged Triller migrates to the ACT each summer, where it is widely distributed in woodlands. A large proportion of sightings are from reserves (Mulligans Flat, Goorooyarroo, the Pinnacle, Black Mountain, Gigerline) and Defence land (Campbell Park).

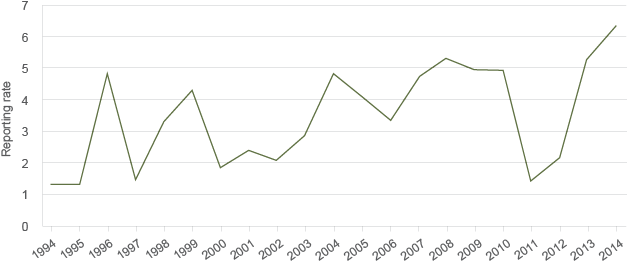

Reporting rates have increased slowly for a long period, with the exception of a sharp dip in 2010–11 and 2011–12 (Figure 7.4). Figures have shown a strong recovery since 2012. There were 17 breeding records in 2013, more than the 10- and 30-year averages for the species.

Source: Canberra Ornithologists Group31

Figure 7.4 White-Winged Triller reporting rates, 1994–2014

Pink-Tailed Worm Lizard

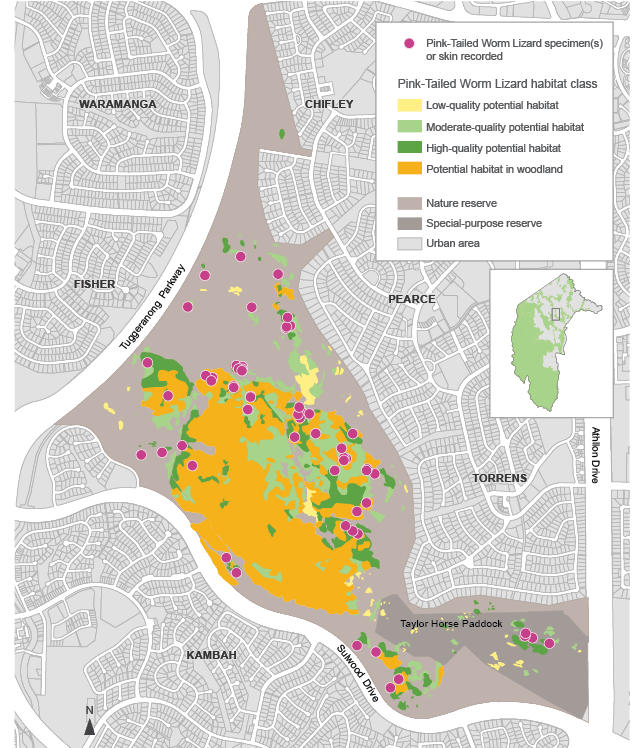

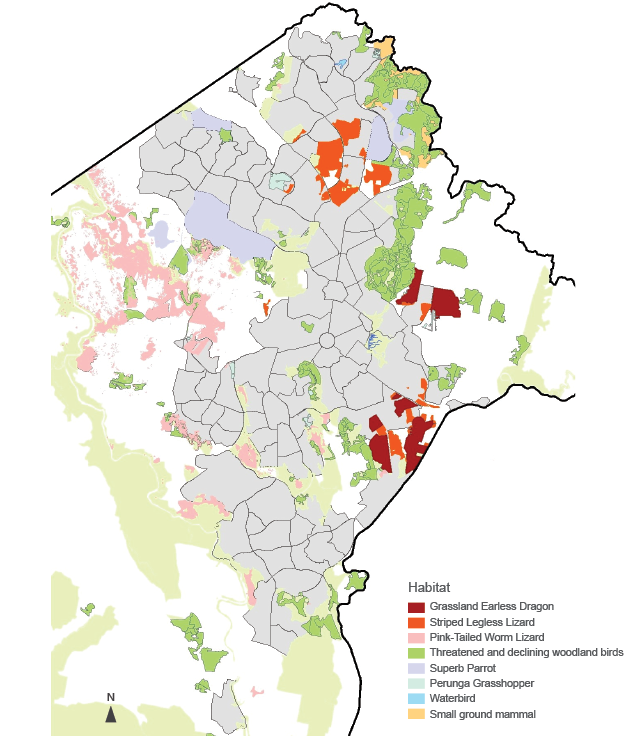

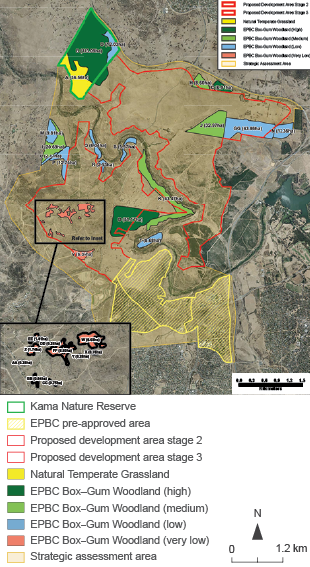

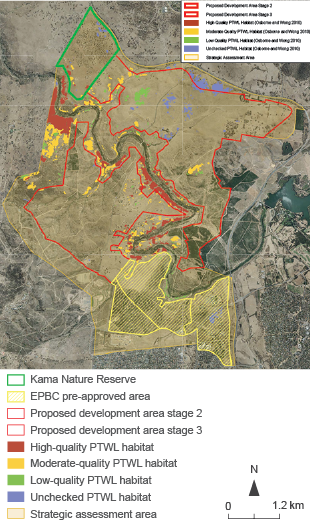

In the ACT, the Pink-Tailed Worm Lizard is mainly distributed along the Murrumbidgee and Molonglo river corridors, as well as in some of the hills within Canberra Nature Park. Although widespread, the species is patchily distributed and is absent from some suitable habitat within larger habitat mosaics. Records have been made in Canberra Nature Park (Mount Taylor, Cooleman Ridge, Urambi Hills, the Pinnacle, Farrer Ridge, Mount Arawang, Oakey Hill, McQuoids Hill, Kama Nature Reserve and Black Mountain), the Murrumbidgee River Corridor (Woodstock, Stony Creek, Bullen Range and Gingerline reserves), some leasehold land and some natural remnants within land managed for forestry. Historical records also exist from within or close to the Ainslie–Majura complex, Tuggeranong Hill and Red Hill.32

The survey results during 2011–2015 are as follows:

- In spring 2012, a detailed survey across the western part of Gungahlin found three live animals and two sloughed skins close to each other in the Kinlyside–Casey area. The Pink-Tailed Worm Lizard was not recorded in any of the pit or tile surveys undertaken for the Striped Legless Lizard across Gungahlin, and was not found in a targeted rock-rolling survey in Moncrieff, Jacka or Taylor. Suitable rocky habitat for this species is generally uncommon in Gungahlin.33

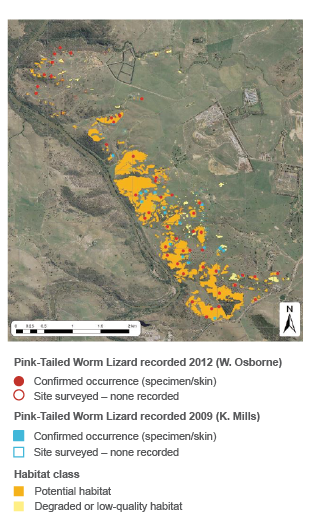

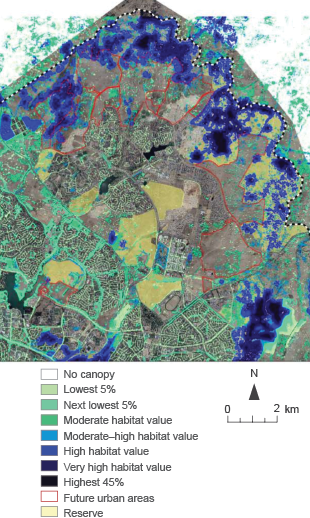

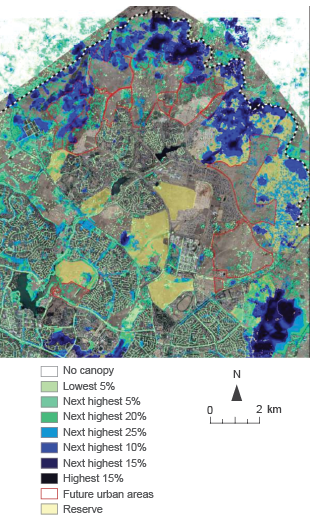

- In 2012, researchers conducted an extensive on-ground confirmatory survey of the current distribution of the Pink-Tailed Worm Lizard within the Mount Taylor Nature Reserve. The study found that Mount Taylor reserve still supports a very substantial and regionally important population of Pink-Tailed Worm Lizards, and this population appears to have changed little in distribution and abundance since the previous comprehensive surveys done 20 years ago.34 Potential habitat for the species in the reserve was found to be widespread and is mostly in good condition – most being mapped as being either moderate (27 ha) or high (20 ha) quality (Figure 7.5).

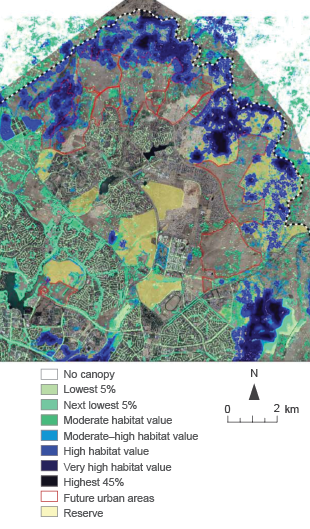

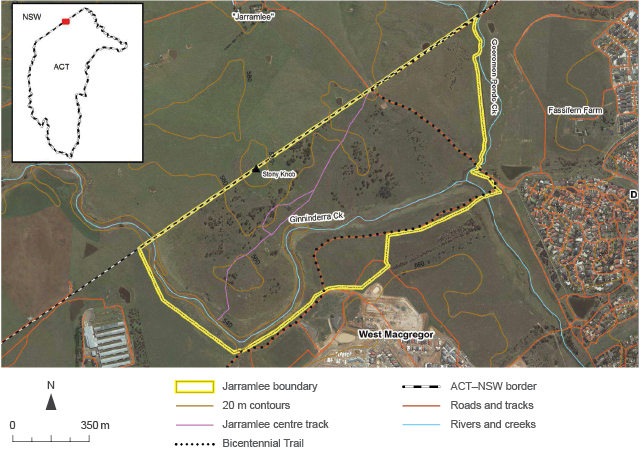

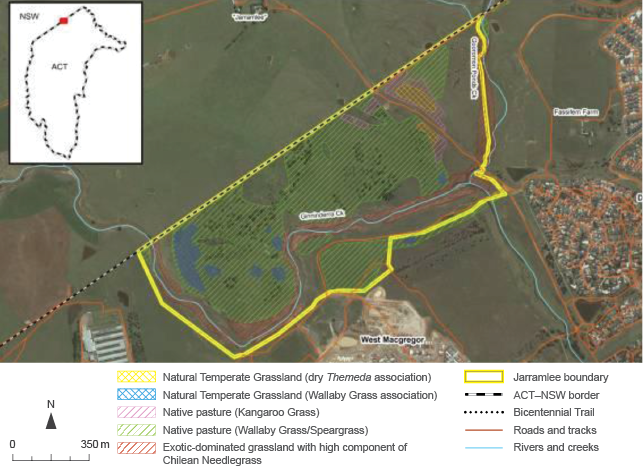

- A 2013 study of habitat for the Pink-Tailed Worm Lizard was conducted in the Belconnen – Ginninderra Creek area. Habitat within the study area contributes greatly to the potential dispersal corridor for Pink-Tailed Worm Lizard and other wildlife species (Figure 7.6). The main corridor in this area is associated with the steeper slopes close to the Murrumbidgee River. The rocky corridor through this part of the ACT and New South Wales (NSW) provides an important link between the biologically diverse Ginninderra Falls area in NSW and the important Molonglo River Corridor in the ACT, where there are many records of Pink-Tailed Worm Lizard along the full extent of the corridor.35

- A 2013 study on a 28-ha rural lease in Pialligo found live lizards, evidence of skins and extensive areas of habitat.36 However, it has recently been confirmed that this habitat is heavily invaded by African Lovegrass.18

Figure 7.5 Locations of Pink-Tailed Worm Lizards in the Mount Taylor reserve plotted in relation to mapped habitat quality, 2012

Figure 7.6 Confirmed location records for Pink-Tailed Worm Lizard overlaid on map of potential habitat, 2013

Striped Legless Lizard

A series of targeted surveys was undertaken between October and December 2012 to provide information on the distribution and density of the Striped Legless Lizard in Crace, Mulangarri and Gungaderra Grassland nature reserves, and adjoining open space. The surveys used an artificial shelter (roof tiles) method with two different grid formations to determine the presence of the species across the three grassland reserve areas.

All reserves support abundant populations of Striped Legless Lizard (Table 7.1). A total of 251 individual animals were identified from a total of 323 captures (including recaptures of the same individual) from the three grassland reserves. Gungaderra recorded the highest number of captures, and the highest density recorded at a single grid was also observed at Gungaderra. With a few exceptions, all grids recorded at least one Striped Legless Lizard capture.

Table 7.1 Summary of Striped Legless Lizard captures in targeted surveys, 2012

| Grassland | Total individuals | Total captures | Capture rate | Number of tiles | Population estimate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Crace |

60 |

84 |

1.7% |

4900 |

1000–3000 |

|

Mulangarri |

90 |

110 |

2.2% |

4900 |

2000–4000 |

|

Gungaderra |

101 |

129 |

2.7% |

4800 |

3000–9000 |

There were 71 recaptures, and most of these were under the same tile, with 84.5% of recaptures within 5 metres (m) of the original capture location. One lizard moved 80 m, while only six recaptures were further than 10 m, suggesting that a 10-m buffer around tile arrays is probably a reasonable indication of the area from which lizards may have been drawn to a tile.

Targeted surveys were conducted in Symonston and Jerrabomberra Valley in 2011. The study area covered four properties totalling 540 ha: Callum Brae, Cookanalla, Bonshaw and Wendover. A small part of the study area also occurred in the Jerrabomberra Grasslands Reserve.

The surveys recorded Striped Legless Lizard individuals at a number of locations. This species predominantly occurred in areas of native grassland dominated by Tall Spear Grass. The estimated density of the lizard within the study area was approximately 19 individuals per hectare. The main population within the study area (east of the Monaro Highway) is considered likely to be contiguous with areas of potential habitat in the adjacent Department of Defence property HMAS Harman and lands to the south-east.37

Murray River Crayfish

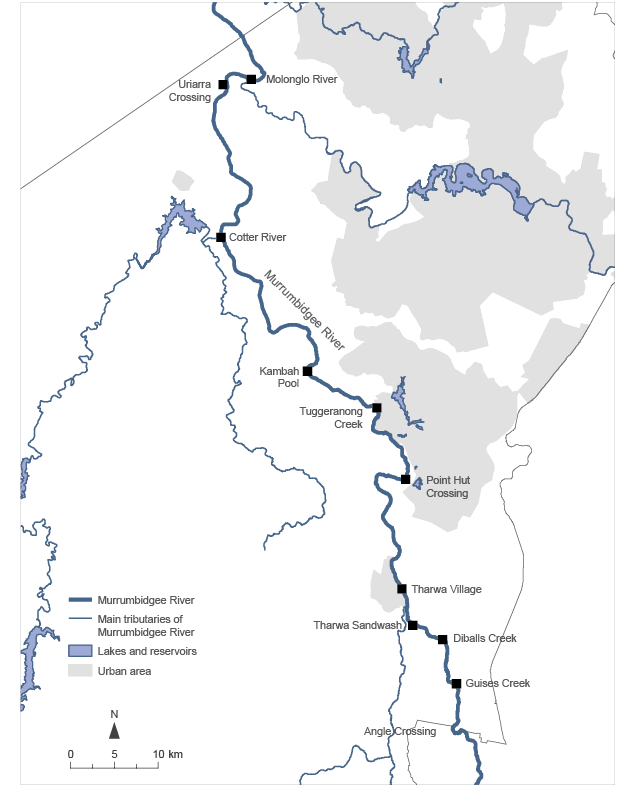

An initial survey of this species in 1988 revealed that, despite evidence of distribution throughout the length of the Murrumbidgee River within the ACT, catch rates were patchy and low in comparison with other parts of its range. In response to these findings, the ACT Government banned fishing of Murray River Crayfish in 1993 and put in place a monitoring program. The low number of crayfish captured longitudinally through this monitoring indicates that the species remains at risk (Table 7.2).38

Table 7.2 Murray River Crayfish captured in the ACT region, 1988–2013

| Area | 1988 | 1989 | 1994 | 1996 | 1998 | 2005 | 2008 | 2013 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Angle Crossing |

0 |

NA |

36 |

5 |

3 |

6 |

NA |

0 |

|

Tharwa Sandwash |

0 |

NA |

18 |

2 |

2 |

0 |

NA |

NA |

|

Lanyon |

0 |

NA |

NA |

NA |

1 |

0 |

NA |

NA |

|

Lambrigg |

0 |

NA |

NA |

NA |

0 |

0 |

NA |

NA |

|

Pine Island (upper) |

1 |

NA |

NA |

NA |

2 |

30 |

2 |

0 |

|

Pine Island (lower) |

NA |

0 |

NA |

NA |

NA |

NA |

5 |

NA |

|

Allens Creek (upper) |

1 |

2 |

NA |

NA |

NA |

NA |

NA |

NA |

|

Allens Creek (lower) |

6 |

2 |

NA |

NA |

22 |

4 |

0 |

8 |

|

Kambah Pool |

1 |

NA |

1 |

5 |

4 |

0 |

0 |

NA |

|

Jews Corner |

5 |

NA |

na |

na |

4 |

0 |

0 |

NA |

|

Casuarina Sands |

0 |

NA |

8 |

2 |

1 |

0 |

5 |

28 |

|

Huntly |

0 |

NA |

NA |

NA |

0 |

0 |

NA |

NA |

|

Uriarra Sandwash |

0 |

NA |

NA |

NA |

NA |

NA |

1 |

NA |

|

Total |

14 |

4 |

63 |

14 |

39 |

40 |

13 |

36 |

NA = not available

Note: Numbers in the table should be interpreted with some caution. Anomalous components of the program have affected confidence in the results and make it difficult to compare trends over time. This is because sampling methods and timing of sampling were not always consistent from year to year. Notwithstanding these issues, Murray River Crayfish is unambiguously a threatened species.

Two-Spined Blackfish

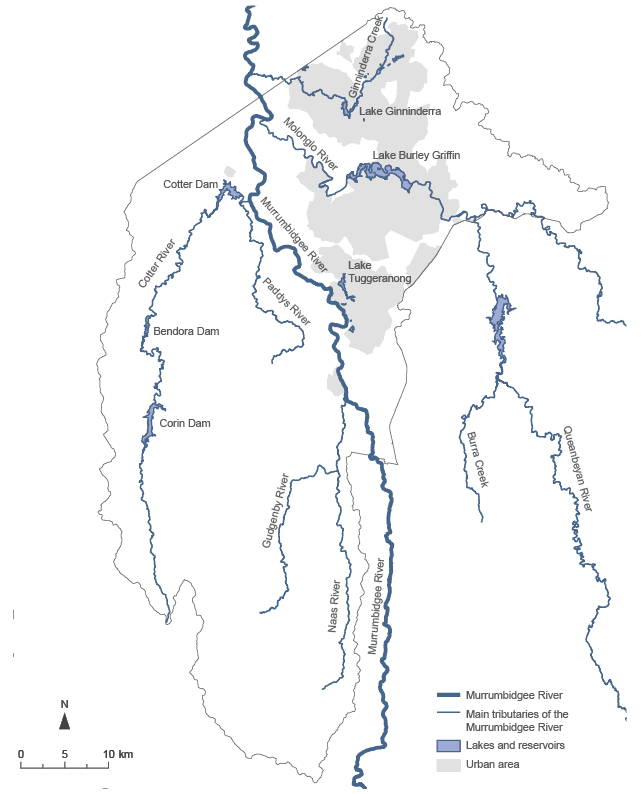

Two-Spined Blackfish are restricted to the Cotter River Catchment within the ACT, and systematic monitoring of the species is undertaken each year.

The monitoring found low numbers of this species in 2009–2012 at both regulated sites (subject to government-controlled Environmental Flow Guidelines) and unregulated sites (upstream of Corin Reservoir). This is likely to be due to drought, followed by extreme high flows during the breeding season.16

The 2013 sampling found that numbers had increased. In 2014, nine Cotter River sites were surveyed. A total of 215 blackfish were caught: 106 from the six sites in the regulated section of the Cotter River and 109 from the three sites in the unregulated section. Two reference sites from outside the Cotter River Catchment were also sampled, where 25 blackfish were caught from Mountain Creek and three from Micalong Creek.

Under the 2013 Environmental Flow Guidelines,39 there are two management indicators for Two-Spined Blackfish populations:

- The first indicator value (40% or more of population at regulated sites being either age 0+ or 1+) was achieved in 2014: 47 of the 106 (44.3%) Two-Spined Blackfish captured from the regulated reach were aged 0+ or 1+.

- The second indicator value (greater than 80 individual blackfish at regulated sites) was also met in 2014, with 106 captured from sites within the regulated reach.

The summarised conclusions from the Two-Spined Blackfish monitoring program in 2014 are as follows:

- The mean number of Two-Spined Blackfish recorded in the regulated reach in 2014 was lower than 2013 but higher than 2012.

- Two-Spined Blackfish resilience to previous flood events is evident, but patterns of response are not consistent among reach types.

- The average abundance of young-of-year (those fish hatched within the current year) appears to have declined; more young-of-year were captured in the regulated than unregulated reach, although the majority of the young in the regulated waterway came from one site (M Beitzel, Aquatic Ecologist, Environment and Planning Directorate [EPD], pers comm, 31 August 2015).

In addition to the 2014 monitoring results for the nine sites presented above, a 2012 study conducted primarily to ascertain the effects of the enlarged Cotter Dam on Macquarie Perch found, for the first time in more than 30 years, Two-Spined Blackfish to be present in the Cotter Reservoir. It is believed that the individuals captured may have been displaced by high flow and/or colonised the backed-up waters of the Cotter Reservoir during the 2011 floods. This provides some indication of how the species may respond to the enlargement of the Cotter Dam.40

As part of assessing the potential impacts on threatened fish from the construction, filling and operation of the enlarged Cotter Dam, sampling for a three-year period (2010–2012) captured 5554 fish from 13 species. Two-Spined Blackfish was the most abundant species captured in the Cotter River.

Perunga Grasshopper

The flightless Perunga Grasshopper is a cryptic species (species that are physically similar but reproductively isolated from each other) that is difficult to detect in grasslands. There have been few detailed studies of this species and, hence, relatively little is known about its habitat requirements or distribution.41 Information on the distribution of this species has generally been collected opportunistically and incidentally while undertaking surveys for plants and other grassland fauna.

The findings of these surveys for 2011–2015 are as follows:

- In 2011, the grasshopper was opportunistically sighted at three different locations within the proposed Molonglo River Corridor Park. It is probable that most of its habitat is within the Molonglo River Corridor, and that measures to improve Pink-Tailed Worm Lizard habitat will also favour this vulnerable grasshopper.42

- Surveys undertaken at lands in Symonston and Jerrabomberra Valley during 2011–12 recorded 14 grasshoppers across three sites.41

- A 2012 survey found two females in the Crace Grassland Reserve.43

Endangered species

A native species is eligible to be included in the endangered category on the threatened native species list if it is not critically endangered, but it is facing a very high risk of extinction in the wild in the near future.

Brush-Tailed Rock-Wallaby

The last recorded sighting of the Brush-Tailed Rock-Wallaby in the wild in the ACT was more than 50 years ago, at Tidbinbilla in 1959.44 There is currently a captive breeding colony at Tidbinbilla Nature Reserve,45 which successfully breeds animals for reintroduction in Victoria and NSW. This program also enables ACT Government ecologists to develop expertise in the ecology and management of the species based on physiological, behavioural and reproductive biology studies of the Tidbinbilla population.

In 2015, a revised version of the action plan for the Brush-Tailed Rock-Wallaby was released in response to new information about the conservation needs of this species.45,46

In addition, the ACT Government is investigating the suitability of possible reintroduction sites within the ACT and the feasibility of re-establishing wild populations that can be maintained in perpetuity at low cost.

However, before a species can be successfully reintroduced to an area, the factors that caused the initial loss must be dealt with. Recent experience in NSW and Victoria suggests that the Brush-Tailed Rock-Wallaby is highly sensitive to low densities of foxes, which means that any reintroduction of this endangered wallaby to the ACT will need a long-term commitment to fox control (Scientific Committee State of the Environment Report reviewer, pers comm by email, 1 October 2015).

Smoky Mouse

In the ACT, there have been only two confirmed sightings (trapped individuals) and a hair record of the endangered Smoky Mouse, all obtained in the 1980s from Namadgi National Park. Follow-up surveys using trapping and hair-sample tubes in the 1990s failed to find the species. Surveys for other small mammal species between 2002 and 2010 also did not record the Smoky Mouse. In 2014, around 40 sites were surveyed using cameras, and the Smoky Mouse was not detected. It is unknown whether this elusive species still persists in the ACT.

Regent Honeyeater

The Regent Honeyeater is a rare visitor to the woodlands of the ACT region, usually attracted by the flowering Yellow Box or suburban ironbarks. It also feeds on nectar from grevilleas and mistletoes, but must compete with the larger and more aggressive Red Wattlebirds and Noisy Friarbirds.

The Regent Honeyeater population is decreasing throughout much of the species’ range, and its range is also contracting. This conclusion, sourced from Australian Government data, is based on a decline in reporting frequency, and the reduced size and occurrence of flocks.47 The ACT Scientific Committee states that the long-term trend does not appear to be towards decline; rather, the data suggest infrequent, unpredictable use of ACT habitat (Scientific Committee State of the Environment Report reviewer, pers comm by email, 1 October 2015).

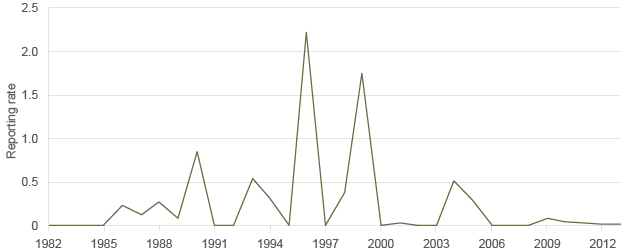

The few records for this bird in the ACT are spread throughout the year and are insufficient to suggest any trend (Figure 7.7).

Source: Canberra Ornithologists Group, http://canberrabirds.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/Regent-Honeyeater.pdf

Figure 7.7 Regent Honeyeater reporting, 1983–2013

Grassland Earless Dragon

The Grassland Earless Dragon is a nationally endangered species, with populations located only near Canberra and parts of the Monaro region near Cooma.

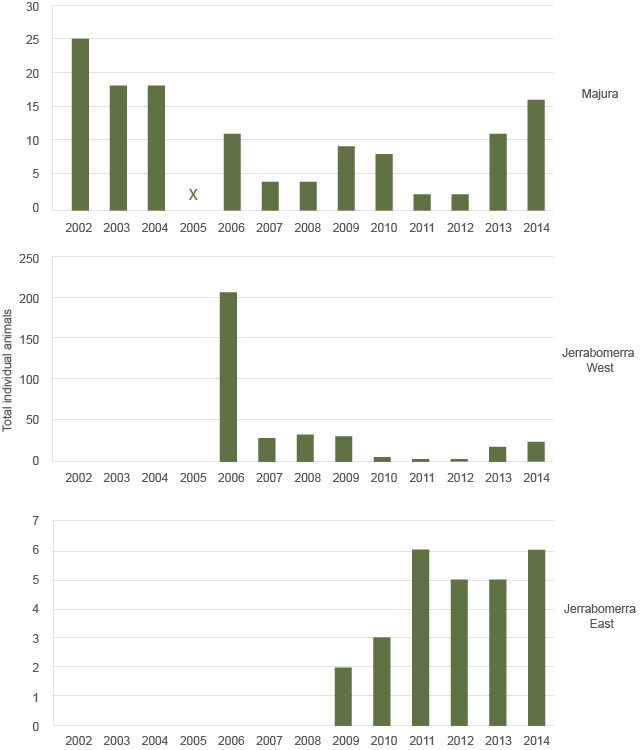

In 2002, a long-term monitoring program using artificial burrows between February and April in each year was set up at Jerrabomberra to:

- determine long-term population trends at key sites

- refine knowledge of the species’ habitat requirements.

The program has found that the species has suffered a serious decline in the past decade (Table 7.3),48 likely due to drought and exacerbated by increased herbivore pressure.

Table 7.3 Grassland Earless Dragons found at Jerrabomberra, 2006–2013

| Age and sex | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Adult males |

24 |

13 |

11 |

6 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

|

Adult females |

18 |

4 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

|

Adult unknown sex |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Juveniles |

165 |

11 |

21 |

22 |

3 |

1 |

0 |

16 |

|

Total |

208 |

28 |

34 |

30 |

5 |

2 |

2 |

18 |

However, since then, numbers have increased at most monitored sites, including Majura Training Area (a Department of Defence site), and East and West Jerrabomberra reserves (Figure 7.8).

Source: ACT Government (Hunting Dragons presentation by the ACT Government to Friends of Grasslands, August 2014)

Figure 7.8 Grassland Earless Dragons found at Majura, Jerrabomberra West and Jerrabomberra East, 2002–2014

With the breaking of the millennium drought in 2010, Grassland Earless Dragon numbers appear to have stabilised and may be recovering.

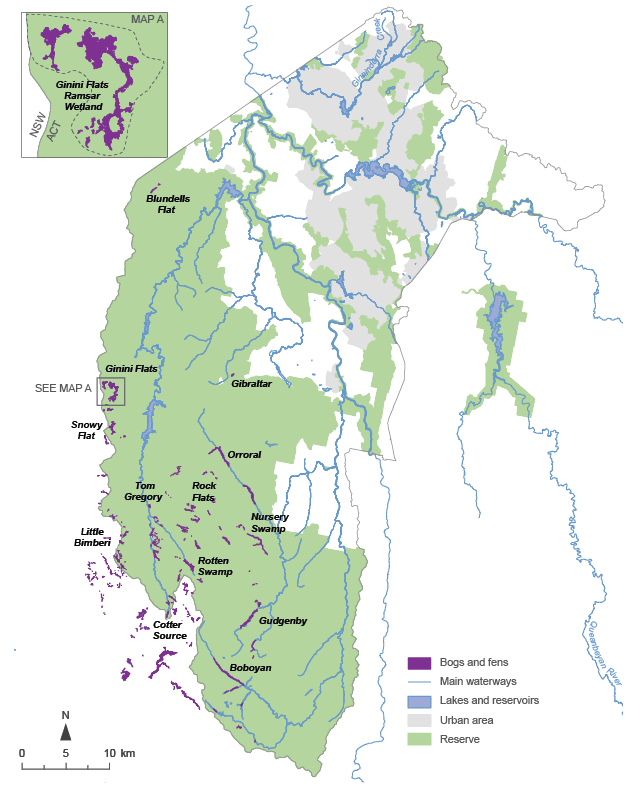

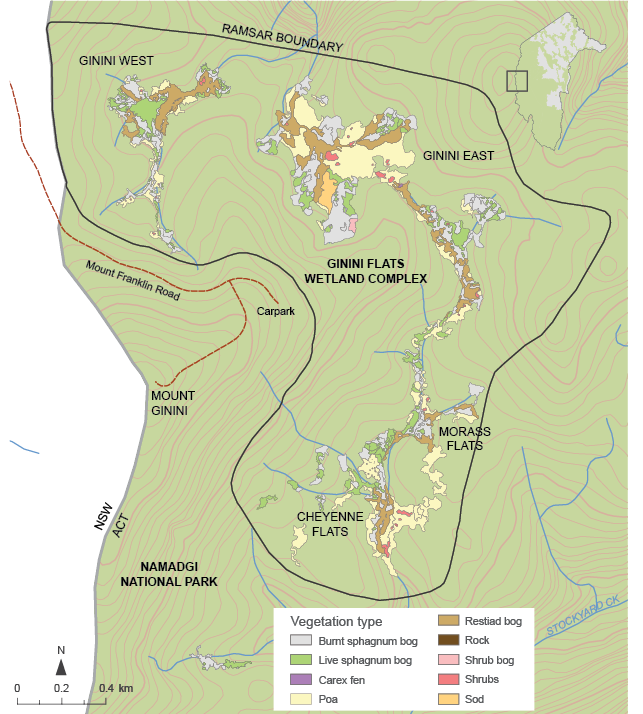

Northern Corroboree Frog

The Northern Corroboree Frog occurs in two isolated populations: one in the Bogong Mountains (Fiery Range, NSW), and the other in the Brindabella Ranges (ACT). The Brindabella Range population occupies the area from California Flats to Mount Bimberi at 1090–1840 m above sea level, and is made up of two subpopulations, each represented by frogs that are slightly genetically different.

The Northern Corroboree Frog disappeared from 40% of its range in the 2000s; declines in the Brindabella Range were more severe.49 There are currently estimated to be fewer than 50 individuals remaining in the wild in this area.16

The decline in the population is due to the spread of the introduced amphibian chytrid fungus, a pathogen that has caused declines, and in some cases extinction, of frogs worldwide.

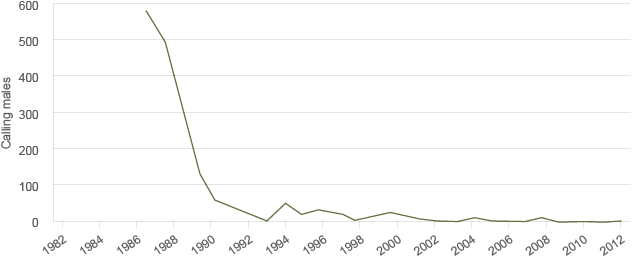

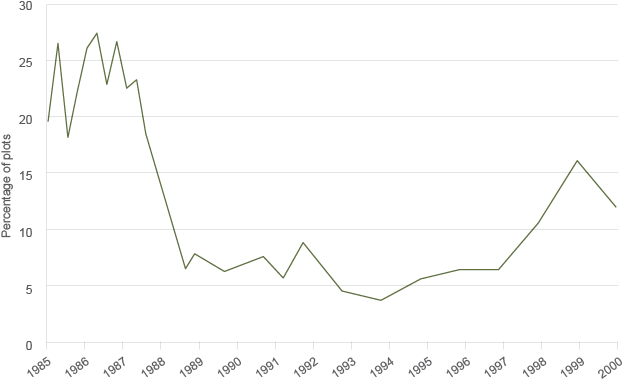

Corroboree Frog monitoring occurs in February each year. The frogs are monitored by counting the number of calling males at breeding sites (sphagnum moss bogs and other wet areas) during the annual summer breeding season (January–March) in Namadgi National Park. Monitoring is done at key breeding sites in the ACT, which include Ginini Flats, Cheyenne Flats and Snowy Flats. In 1985, there were more than 500 males calling at Ginini Flat West (Figure 7.9), but, since 2002, there have been fewer than five males calling during the surveys.

Figure 7.9 Northern Corroboree Frog abundance at Ginini Flat West in Namadgi National Park, 1982–2012

There are now too few Northern Corroboree Frogs remaining in Namadgi National Park to breed and maintain wild populations. For this reason, CPR (ACT Government) established a captive population of Northern Corroboree Frogs from eggs collected in the wild in 2003. The captive population is located at Tidbinbilla and currently houses around 500 frogs.

Juvenile Northern Corroboree Frogs bred in captivity were released back to sphagnum moss bogs in Namadgi National Park in 2011 and 2012 to determine whether such releases can bolster wild populations, and promote breeding and development of natural resistance to chytrid fungus.

Field monitoring in February 2015 showed that some of the captive-bred individuals released in 2011 to the wild have survived to breeding age.

Macquarie Perch

The Australian Government Species Profile and Threats Database reports that, in the ACT, Macquarie Perch is restricted to the Murrumbidgee, Paddys and Cotter rivers. It was previously known to occur in the Molonglo River, but was last recorded in the river in about 1980.50

The Macquarie Perch has evolved in riverine systems and requires access to flowing water to breed. This has meant that lack of access to the Queanbeyan River following filling of Googong Reservoir has led to the near-extinction of an impoundment population of Macquarie Perch. The Queanbeyan River/Googong population was translocated above the Googong Reservoir – it survived for a while, but after the drought it has not been recaptured and is presumed extinct.

Adult Macquarie Perch usually remain within Cotter Reservoir and had previously not been observed in the Cotter River during an annual cycle. However, there is now a resident population of the species in the river.

The mechanisms underpinning the adult occupation of Cotter Reservoir, and the avoidance of river habitat for much of the year, are poorly understood. Potential reasons include dominance of alien salmonids in the river upstream, differential predation by avian predators in the river relative to the reservoir, thermal conditions, in-stream barriers as a result of a relatively steep gradient riverbed coupled with low and regulated flows, or angling pressure.51

Sampling during a three-year period (2010–2012) shows that, from a total of 5554 fish from 13 species captured, Macquarie Perch was the most abundant species captured in Cotter Reservoir.

Silver Perch

The once-strong Silver Perch population in Burrinjuck Reservoir (NSW) collapsed in the 1980s. There was a concomitant collapse of that population’s annual summer migrations into the ACT reaches of the Murrumbidgee River. This collapse was captured in data from a fish-monitoring trap on the Murrumbidgee River at Casuarina Sands, in which Silver Perch captures declined from 252 specimens in 1984, to 4 in 1988 and none in 1989. (Severe drought also impeded fish movement in the first three years of the trap’s operation.) Since 1990, no Silver Perch have been recorded in the ACT reaches of the Murrumbidgee River in fish surveys and monitoring. Similarly, monitoring at two sites in Burrinjuck Reservoir in 2004 failed to locate any specimens.52 Silver Perch is now functionally extinct in the ACT (L Evans, Senior Aquatic Ecologist, Conservation Research, EPD, pers comm, 17 June 2015 ).

Trout Cod

Trout Cod died out in the Canberra region in the 1970s. Conservation stocking has been undertaken in a number of waterways as part of the National Recovery Plan for Trout Cod in an effort to re-establish the species in its former range.16

Historically, Trout Cod occurred throughout the entire length of the lower Murrumbidgee River and 200 kilometres (km) of the upper Murrumbidgee; the species was last recorded from the river in 1976. In an attempt to restore Trout Cod populations, both the upper and mid-reaches of the Murrumbidgee River have been stocked. In excess of 326 000 Trout Cod fingerlings have been stocked across eight sites in the upper Murrumbidgee River since 1988. Regular monitoring at some sites has demonstrated survival and growth of stocked individuals, but no recruitment or establishment of self-sustaining populations has occurred. Detection of stocked individuals 3+ years old at riverine sites has been unsuccessful, except at one site where 3-year-old Trout Cod are being regularly recorded.

Angle Crossing received the greatest stocking effort (99 500 fingerlings over nine years to 2005), and the collection of a single small fish in 2011 (six years after stocking ceased) may be an indication that some breeding by stocked fish has occurred. Stocking of 8740 fingerlings over two years in Bendora Reservoir on the Cotter River has resulted in recruitment from stocked fish more than a decade after stocking, and these recruits now dominate the population.18,53

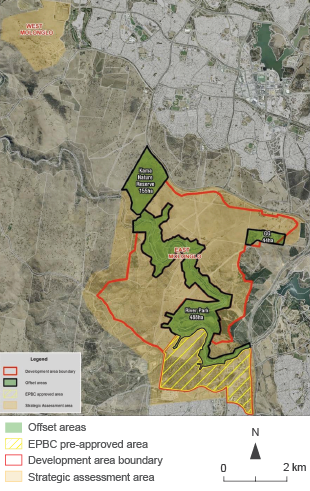

Golden Sun Moth

Surveys of Golden Sun Moth show that there is a total of 1800 ha of moth habitat in the ACT.54 Of this, 47% is within existing or proposed nature reserves, or existing or proposed offset areas; 21% is approved or proposed for clearance; and 23% occurs on Commonwealth land and has an uncertain future.

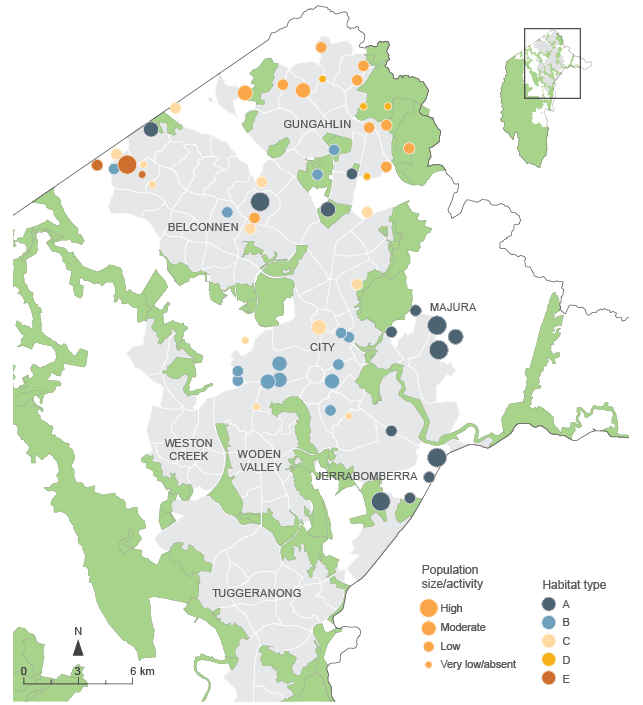

Potential moth habitat includes areas of Natural Temperate Grassland and nearby open woodlands (medium probability), and native grassland containing significant Wallaby Grass and/or stipa cover (high probability). There are 73 habitat sites identified in the ACT (Figure 7.10), but most sites are fragmented and isolated. This is important for the long-term protection and conservation of the species; given the moth’s poor flying ability, populations separated by distances of greater than 200 m can be considered effectively isolated.

Notes:

1. Habitat type A. Natural Temperate Grassland/high-quality native pasture – large area.

2. Habitat type B. Natural Temperate Grassland/high-quality native pasture – smaller remnant.

3. Habitat type C. Mixed native and exotic grasses in former Natural Temperate Grassland.

4. Habitat type D. Secondary grassland (Box–Gum Woodland community).

5. Habitat type E. Chilean Needlegrass or other exotic grasses.

Source: Adapted from Hogg & Moore56 in Mulvaney,33 p 58

Figure 7.10 Distribution, habitat type, population size and activity of Golden Sun Moth across the ACT, 2012

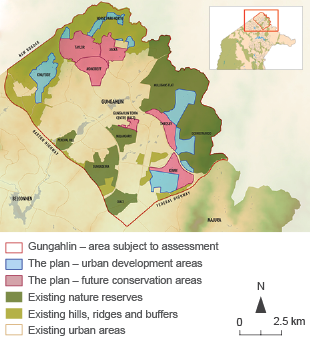

Gunghalin contains 45% of the ACT’s moth habitat, but only 9% of the population (as recorded by maximum moth counts; Table 7.4). In terms of number of sites, habitat area and moths supported, the Jerrabomberra Valley appears to be the least important of the five valleys in which the Golden Sun Moth occurs. However, the Commonwealth land in Jerrabomberra is perhaps the last large high-potential habitat area yet to be surveyed – which, if surveyed, may change the figures.

The ACT Strategic Conservation Management Plan for Golden Sun Moth was released in 2012.55

Table 7.4 Golden Sun Moth sites, habitat and numbers in ACT valleys

| District | No. of sites | Habitat area (ha) | Percentage of habitat | Max no. of moths | Percentage of moths |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Belconnen |

9 |

355 |

20 |

3083 |

27 |

|

Central Canberra |

25 |

110 |

6 |

1484 |

13 |

|

Gungahlin |

32 |

812 |

45 |

991 |

9 |

|

Jerrabomberra |

7 |

60 |

3 |

502 |

4 |

|

Majura |

5 |

466 |

26 |

5444 |

47 |

ha = hectare

The Golden Sun Moth is an endangered species in the ACTPhoto: ACT Government

Baeuerlen’s Gentian

The only confirmed site of Baeuerlen’s Gentian – a small annual subalpine herb – is in the Orroral Valley in Namadgi National Park. In 1992, the ACT subpopulation had 20 plants; in 1994, it had 4 plants. The species has not been seen in the ACT since 1998, and annual surveys in the Orroral Valley between 2002 and 2013 have failed to detect the species.57

Brindabella Midge Orchid

Since 2009, CPR has conducted annual monitoring of the Brindabella Midge Orchid population in late summer to early winter. In 2013, the survey methodology was changed to account for the recent finding that the orchid flowers nearly all year round.

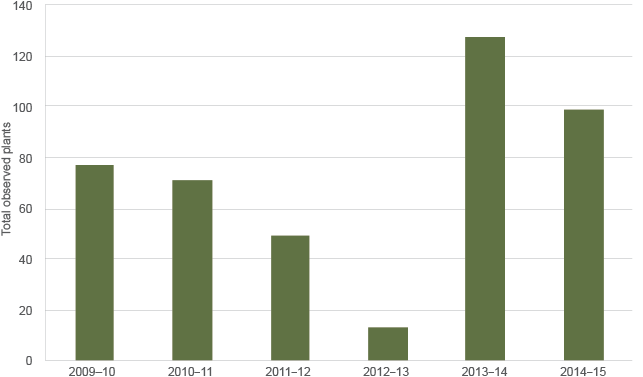

After four years of decline, a large number of individuals were observed in 2014 and 2015 (Figure 7.11). This is consistent with reports that emergence and flowering of many orchid species vary widely from year to year, including threatened Australian orchids and overseas species. Climatic factors, as well as past flowering history of individual plants, may play a role in this interannual variability. However, little is known about the ecology, lifecycle and preferred conditions of this species.

Note: In 2012–13, the monitoring methodology was changed, and data from that year on represent the minimum number observed. Numbers for other years have been adjusted to include only plants observed over the same survey area.

Figure 7.11 Total count of Brindabella Midge Orchids, 2009–2015

The minimum number of plants known to have emerged in 2014 was 127; in 2015, it was 99, representing the largest number of emerging plants observed across the survey zone since annual monitoring began in 2009–10. Individuals were observed along the length of the monitored transect.

Button Wrinklewort

In December 2012, CPR qualitatively surveyed the habitat conditions of the known Button Wrinklewort populations, and identified any threats and mitigation actions that were required (Table 7.5).16 Although estimates provide a representation of the true population size at each location, estimates are often inaccurate by an order of magnitude when compared with counts of individuals. Resource constraints do not currently permit an individual count of this species, so estimates continue to be used to estimate population health.16

Table 7.5 Known Button Wrinklewort populations, threats and required mitigation actions, 2012

| Location | Observation | Threats | Recommended action |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Kintore Street |

No plants found; good native forb, and grass cover and diversity |

Mowing |

Resurvey December 2013 |

|

Baptist Church, Kingstona |

At least 71 plants, most flowering and healthy |

Car parking, mowing |

Improved management of car park |

|

St Marks, Bartona |

At least 31 plants, most carrying seed |

Biomass accumulation, woody weeds |

Burning of site, weed removal |

|

Campbell offices |

Estimated 80–90 plants found in 6 extant subpopulations; no plants found in one previously recorded small subpopulation |

Weeds (St John’s Wort) |

Weed control |

|

Tennant Street, Fyshwicka |

>400 plants counted; many seedlings observed and most plants carrying seed; site in good condition |

Minor weeds |

Weed control |

|

Woods Lanea |

At least 150 plants found across the 3 subpopulations; >38 plants counted in the northernmost population where no plants were seen in 2012 (3 of the 6 subpopulations were burnt in 2014 to reduce biomass) |

Road construction, infrastructure development, rubbish dumping (especially at the central site), weeds (St John’s Wort, wild oats) |

Improved roadside signage, weed control, rubbish control |

|

Stirling Ridge |

Estimated 1500–2000 plants, noting difficulty in estimating large populations over such a big area; overall, this site is in good condition with some weed issues |

Weeds |

Weed control |

|

Attunga Point |

Estimated 40–50 plants in fenced-off location with good native species cover |

None recorded |

None |

|

Blue Gum Point |

Estimated 250–300 plants; area is affected by regular mowing and weeds |

Mowing, weeds |

Weed control, improved mowing regime |

|

State Circle |

At least 20 plants |

Weeds (St John’s Wort, Cootamundra Wattle) |

Weed control |

|

Crace |

Site in good condition; no estimate of population size available |

None recorded |

None |

|

Jerrabomberra East Nature Reserve |

Translocated population in good condition; no estimate of population size available |

None recorded |

None |

|

Red Hill |

Sites in good condition with little change in population size; no estimate of population size available |

None recorded |

None |

|

HMAS Harman |

Site not monitored by ACT Government |

None |

None |

|

Majura Training Area |

Site not monitored by ACT Government |

None |

None |

a Updated 2015.

Canberra Spider Orchid

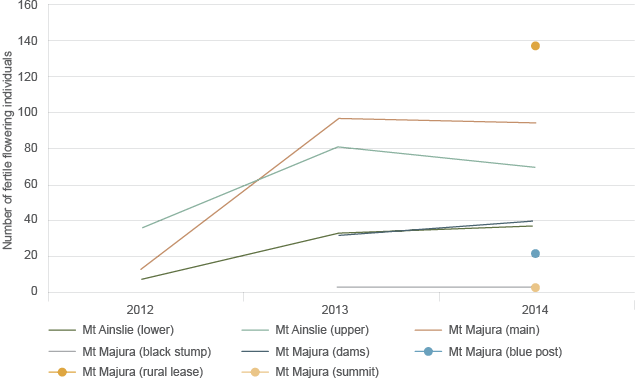

The Canberra Spider Orchid is a small terrestrial orchid that flowers sporadically along the slopes of Mounts Ainslie and Majura, and within the Majura Valley on land managed by the Australian Government Department of Defence at the Majura Training Area. A third and most recently discovered population is to the east of the Majura Valley in the Kowen Escarpment Nature Reserve. There are two other records of the species in the suburbs of Campbell and Aranda before their development; however, it has not been recorded in these areas for more than a decade. The species is not known to occur outside of the ACT.

The species is monitored on Mounts Majura and Ainslie during the flowering season by counting plants occurring in the known population areas. Details recorded include numbers of fertile flowers, pollination rates and incidence of grazing.

During the prolonged drought conditions in the early 2000s, very few individuals were recorded. In the past six years, there have been clear signs of recovery, and numbers appear stable with expected fluctuations due to seasonal conditions. More individuals were recorded in 2014 than in any previous year since 2012 (Figure 7.12).

Figure 7.12 Canberra Spider Orchids recorded, number and location, 2012–2014

Two new subpopulations were discovered during the flowering season in 2014 by members of the public: on Mount Majura outside of the nature reserve and in the eastern foothills of Mount Ainslie. Another small new population was also located by a member of the public in the Kowen Escarpment Nature Reserve. The Mount Majura subpopulation was inspected by CPR staff in September 2014, and they recorded 138 plants across a 10 m × 10 m area. The remaining subpopulations consist of only a few plants each, and will be visited and inspected by CPR staff in spring 2015.

Habitat conditions are monitored annually, and threatening processes are addressed through management actions. Two fenced enclosures and a new set of small cages have been successfully used to reduce damage caused by kangaroos and rabbits on Mounts Majura and Ainslie. CPR has written a translocation plan as part of an Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (Cwlth) (EPBC Act) assessment to prepare to translocate this species. However, further work is required to determine pollinator distribution and habitat characteristics before planting occurs. Translocation of the Canberra Spider Orchid is used in conjunction with threat management to improve the ecological resilience of the species.

Ginninderra Peppercress

Ginninderra Peppercress is endemic to the ACT and was first described in 1970 from a single collection in the suburb of Reid, but has not been seen in Reid since then. The plant was not seen again until 1993 when it was found on the floodplain of Ginninderra Creek in the Belconnen Naval Transmission Station. In 2001, the species was formally described. In October 2013, a small population was located by Nicki Taws (Greening Australia) in an area of Special Purpose Reserve in Mitchell.

The Naval Station is managed by the Australian Government Department of Defence, which monitors this species. The population has varied considerably, from a minimum of fewer than 50 plants in 1997 to a maximum of 3523 in 2006. The most recent estimate is 1137 in 2009.

At the Mitchell site, CPR staff conducted a population census in October 2012, and 50 plants were counted. All of these were tagged to help determine lifecycle characteristics of the species. In 2013–14, additional subpopulations were found by various local botanists, some of whom collected information about its abundance. For example, in 2014, Rob Armstrong reported counting four subpopulations, including the plants tagged by CPR. He located 32 individuals in the tagged subpopulation (a decline of 18 plants) and another 72 plants scattered across three additional subpopulations. In 2015, CPR undertook a more comprehensive survey of the north Mitchell grasslands. A total of 377 plants from five separate subpopulations were found. Seedlings were observed, and many plants were carrying seed. It is apparent from the variance in survey results across years at both sites that the number of individuals may vary greatly depending on site conditions (R Armstrong, Senior Ecologist, Umwelt [Australia], pers comm by email, 2 October 2015).

Between 2002 and 2008, seed was collected by the Australian National Botanic Gardens (ANBG) from the Lawson population and has been successfully germinated. By 2013, the ANBG seed bank contained more than 99 750 Ginninderra Peppercress seeds. Additions to the seed bank were made in 2015 from CPR collections at the north Mitchell population.

In the spring of 2013, Greening Australian, CPR, the ANBG and the ACT Parks and Conservation Service (PCS) translocated plants grown from seed collected or originating from the Lawson population into Crace (1050 plants) and Dunlop Nature Reserve (500 plants). Unfortunately, despite follow-up watering by Greening Australia, it appears that both translocation attempts failed. No live plants have been observed at either site since the end of summer in 2013. A number of factors could have contributed to this failure, including potting mix that may have become hydrophobic after planting, an especially hot summer (47 days reached 30 °C or more), and a very dry February and March. Further translocation efforts may test other ways of establishing new populations of the species.

Murrumbidgee Bossiaea

Murrumbidgee Bossiaea (B. grayi) was first described in 2009 when B. bracteosa was taxonomically divided into four new species (Scientific Committee State of the Environment Report reviewer, pers comm, 1 October 2015). In 2012, Murrumbidgee Bossiaea was declared a threatened plant species in the ACT under the Nature Conservation Act. Accordingly, Action Plan 34 was created to define conservation measures for the species, which include surveying and monitoring the ACT population. In spring 2013, the plants were surveyed to confirm the presence and size of Murrumbidgee Bossiaea populations at a number of ACT locations. Information was also collected on critical habitat parameters and any perceivable threatening processes. This will be used to inform management of the species in the ACT, as well as to inform the development of a long-term monitoring strategy.

These surveys identified 10 discrete population clusters in the ACT, with an estimated total population size of 2700–2900 individuals. Five distinct population clusters occur on the Murrumbidgee River, four distinct populations on Paddys River and one plant on the lower Cotter River. The species was recorded at elevations of 445–575 m. Landscape position and soil type seem to be the main drivers of where population clusters appear; all sites are located within incised river valleys, mostly on steep, rocky and skeletal soils.

The overall population size of Murrumbidgee Bossiaea suggests that immediate loss of the species is unlikely except in the event of an unforeseen impact. However, there are a number of small disjunct population clusters on the Paddys and Cotter rivers that are highly vulnerable, and their loss could lead to a range reduction. Given that all population clusters are disjunct, it is not clear if any genetic separation has occurred.

Most population clusters occur on reserved land, although three (including the two largest groups) are outside of reserve area within land designated as ‘mountains’ and ‘bushland’ under the ACT Territory Plan (see Chapter 5: Land). The major identified threats to the species include competition from native shrubs, low numbers and the isolation of some population clusters.

In 2014, CPR, the ANBG and volunteers collected seeds from 120 individuals from the two largest populations along Paddys River. A total of 21 965 seeds are held in storage at the National Seed Bank.

In 2015, seed germination trials were conducted by the Australian Native Plants Society. Preliminary results indicate that treatment of seed by either microwave heating, immersion in 95 °C water for two minutes or scarification with sandpaper significantly increases the proportion of seed germinating compared with untreated seed. Further germination and propagation trials will be conducted to increase knowledge on conservation options for this species.

Small Purple Pea

Five sites within the urban areas of Canberra have been known to support populations of the endangered Small Purple Pea. The largest of these populations occurs in the Mount Taylor Nature Reserve, with more than 300 plants recorded since surveying began in 2001. This site was severely burnt in the 2003 bushfires. A small population of approximately 10 plants exists on a vacant urban block in the suburb of Kambah, which has been fenced to protect the population. Small numbers of plants have also been recorded in the past at sites on Long Gully Road, at a rural block on Caswell Drive and at Farrer Ridge.

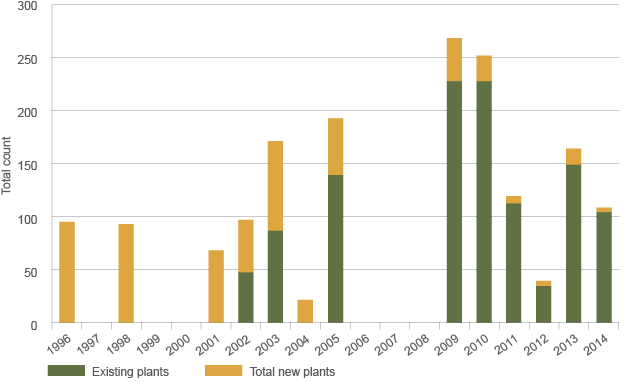

Monitoring of the Mount Taylor site indicates that – although this population has been stable, with numbers steadily increasing since plants were first tagged in 2001 – in 2011 there was a 53% decrease in abundance from the previous year. This increased to 68% in 2012. A number of factors may have influenced these declines, including rainfall, predation, ground temperatures, moisture levels and intraspecific competition. It is also likely that both the decreases and increases in abundance are, in part, due to natural population fluctuation, because the species is known to have dormancy periods of anywhere from one to nine years.58 In 2004, to avoid overly trampling the site and new regrowth after the fire in 2003, a full survey was not carried out, and only untagged plants were recorded and tagged (Figure 7.13). Recruitment levels have steadily dropped since the peak abundance in 2009.

Figure 7.13 Small Purple Pea recordings at Mount Taylor, 1996–2014

The population at McTaggart Street in Kambah appears stable despite no increase in annual flowering plants since surveying began in 2002 (Table 7.6). It should be noted that in 2012 only one plant was recorded, and it suffered grazing after initial observation. General site condition and diversity are very good, with large numbers of disturbance-sensitive forbs present in the spring of 2013. It would appear that there has been a positive response to the most recent burn, with widespread flowering and growth of native species, and limited spread of broadleaf and woody weeds. A total of 23 plants have been tagged at this site. Many of these individuals have not been recorded for a number of years, and no new plants have been identified since 2003.

Table 7.6 Small Purple Pea abundance, McTaggart Street, Kambah, 2000–2014

| Year | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011a | 2012 | 2013 a | 2014 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Total plants |

10 |

7 |

10 |

7 |

10 |

7 |

8 |

8 |

1 |

9 |

8 |

a Ecological burn in June of this year.

The Caswell Drive population was thoroughly searched by ecological consultants from Biosis. The same two plants from 2013 were located, with developed flowers and pods.

Tarengo Leek Orchid

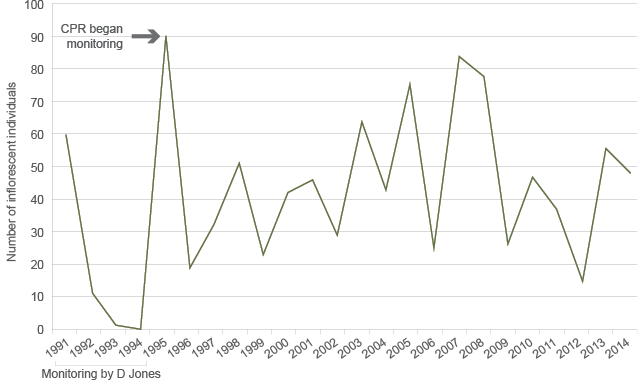

This small orchid only occurs at a site in Hall in the ACT, along with five other sites with small populations in NSW. CPR monitors the Tarengo Leek Orchid each year.59 The abundance of this species fluctuates each year, with a very weak, positive trend (Figure 7.14). Population fluctuations do not appear to be correlated with weather patterns. Given the large fluctuations in numbers, it is imperative to continue monitoring this species every year, and for researchers to work closely with site managers.

CPR = Conservation and Planning Research

Figure 7.14 Tarengo Leek Orchid abundance, Hall Cemetery, 1991–2014

Tuggeranong Lignum

Since 1999, a series of surveys and opportunistic sightings have identified a total of 13 individuals of Tuggeranong Lignum – a sprawling woody shrub – on the eastern bank of the Murrumbidgee River. In 2013, all of these plants were still alive. No plants are known to persist on the western bank of the river. A survey in February 2015 found that 12 of the plants were still alive. A male plant, first observed in 1997 on the banks of the Murrumbidgee, appears to have died. This plant was in an area subject to a great deal of disturbance from flooding and sand movement, and was also being encroached upon by Blackberry.

Translocation of clonally grown Tuggeranong Lignum has been attempted on a number of occasions since 2010. Initially, 93 plants were translocated into the Murrumbidgee River Corridor in locations close to the wild plants. None of these plants are known to have survived; there are a number of possible causes for this failure, including extensive flooding and heavy weed infestation at the site. In 2013, CPR staff translocated 19 plants into suitable habitat on Point Hut Hill and another 17 plants into Bullen Range Nature Reserve near the old record from Red Rocks Gorge. All of the plants translocated into Bullen Range have since died. However, as of February 2015, 10 plants still persist at Point Hut Hill. Anecdotal observations of these plantings indicate that plants on sheltered southerly aspects appear to survive longer than on other aspects.

In 2013, CSIRO performed genetic testing to identify how many wild individuals there were (plants sprawl across each other in some sites, making it difficult to determine numbers by observation) and how many of these genotypes are reflected in the surviving translocated plants. Unfortunately, the results were inconclusive due to the limited number of loci that could be used in the analysis.

Following the loss of one of the wild individuals, CPR and the ANBG decided to collect material from all 12 wild plants and 10 translocated plants so that the species could be propagated. This project is designed to secure the current genetic diversity of the species by having at least one representative of each plant growing in the permanent collection at the ANBG. Additional material grown by ANBG may be made available for future translocation attempts.

Threatened ecological communities

Why is this indicator important?

An ecological community is defined as a naturally occurring group of native plants, animals and other organisms that are interacting in a unique habitat. The community’s structure, composition and distribution are determined by environmental factors such as soil type, position in the landscape, altitude, climate and water availability.

The native plants and animals within an ecological community have different roles and relationships that, together, contribute to the healthy functioning of the environment and to the provision of ecosystem services.

Current monitoring status and interpretation issues

Reporting for this indicator focuses on the ecological communities listed as threatened under the ACT Nature Conservation Act or the EPBC Act. The ecological communities are generally described in terms of the main vegetation type (eg Yellow Box – Blakely’s Red Gum grassy woodland, Natural Temperate Grassland). This indicator reports on the state and/or trend of the extent and, where possible, the condition of each listed threatened ecological community. Although the indicator focuses on the extent and condition of the main vegetation type, it is assumed that this also indicates the state of the ecological community as a whole.

The quality and quantity of the reporting are commensurate with the monitoring data available in the reporting period.

Where data are available, the extent and condition of nonlisted communities are reported under ‘Other ecological communities’.

Vegetation condition can be assessed from a number of different perspectives, such as degree of land cover or degradation, ecological productivity and regeneration capacity, production capacity for economic goods, extent and type of past disturbance, presence of different plant species, or important habitat features for wildlife. Vegetation in good condition from one perspective (eg grazing) may be in poor condition from another (eg supporting native biodiversity conservation). In the ACT, there does not appear to be any consistency in the use of different vegetation condition monitoring systems.

There are also significant challenges involved in the analysis and presentation of data for this indicator. This is because the relevant reports and data all contain different methods for classifying (and therefore surveying and mapping) ecological communities, particularly woodlands. The report by Maguire and Mulvaney60 provides a reasonable estimate (based on best available data at the time of publication) of the extent of EPBC Act condition and ACT-listed woodland across the ACT (figures are in the report). There are no comparable figures for other woodland types or open forest. This issue has been compounded by the lack of consistent vegetation classification or mapping within the ACT. These anomalies mean that it has not been possible to accurately report on the extent and condition of ecological communities in the ACT in this reporting period.

Significantly, this matter is in the process of redress. Using a standard classification system, the ACT vegetation and ecological communities are currently in the process of being mapped, based on the methods described in Armstrong et al.61

What does this indicator tell us?

Section 101 of the Nature Conservation Act requires the Conservator of Flora and Fauna to prepare an action plan for each species or ecological community that has been declared vulnerable, critically endangered or endangered. Action plans must contain proposals for the identification, protection and survival of the community or species, including the identification of any critical habitat.

The ACT has three broad strategic action plans, which include action plans for ecological communities and individual action plans for species:

- The ACT Lowland Woodland Conservation Strategy (Action Plan 27) contains nine individual plans (Brown Treecreeper, Hooded Robin, Painted Honeyeater, Regent Honeyeater, Small Purple Pea, Superb Parrot, Swift Parrot, Tarengo Leek Orchid, Yellow Box – Blakely’s Red Gum grassy woodland).

- The ACT Lowland Native Grassland Conservation Strategy (Action Plan 28) contains six individual plans (Grassland Earless Dragon, Striped Legless Lizard, Golden Sun Moth, Perunga Grasshopper, Button Wrinklewort, Natural Temperate Grassland).

- The ACT Aquatic Species and Riparian Zone Conservation Strategy (Action Plan 29) contains five individual plans (Macquarie Perch, Murray River Crayfish, Trout Cod, Two-Spined Blackfish, Tuggeranong Lignum).

This indicator reports on the subjects of the three broad action plans.

Woodlands

Extent of ACT-listed woodlands

In 2011, mapping was completed of the extent of Yellow Box – Blakely’s Red Gum grassy woodland (Box–Gum Woodland) listed under Australian Government and ACT legislation. This reinterpreted data collected in 1995–97 and 2001–05.60

Across the ACT, 13 765 ha of Box–Gum Woodland was mapped. The current nature reserve network contains 5699 ha of Box–Gum Woodland, including 3364 ha of woodland that meets the listing criteria under the EPBC Act. For both the total remaining extent of Box–Gum Woodland listed under ACT legislation and that component of the ACT total listed under the EPBC Act, a little more than 40% is within the ACT conservation reserve network.

Since the previous mapping in 2004, about 1206 ha (including 933 ha of woodland listed under the EPBC Act) has been added to the reserve network, and around 192 ha of woodland has been lost to urban development (Table 7.7).

Table 7.7 Extent of listed Yellow Box – Blakely’s Red Gum grassy woodland in the ACT

| Box–Gum Woodland | Total extent mapped in 2004 (ha) | Total extent mapped in 2011 (ha) | Woodland lost to urban development since 2004 (ha) | Woodland in conservation reserves (ha) | Woodland added to reserve network since 2004 (ha) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

ACT-listed |

12 034 |

13 765 |

192 |

5 699 |

1 206 |

|

Commonwealth-listed |

Not mapped |

8 151 |

Unknown |

3 364 |

933 |

ha = hectare

Note: Determination of the extent of Box–Gum Woodland listed under the Nature Conservation Act 2014 (ACT-listed) and the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (Commonwealth-listed) requires ground validation by skilled ecologists in many cases, and it is likely that the actual figures vary from that shown in this table. This means that it is possible that Commonwealth-listed Box–Gum Woodland is underestimated, and ACT-listed Box–Gum Woodland is overestimated.

Source: Umwelt in ACT Scientific Committee18

Overall, the 2011 mapping identified 1731 ha more Box–Gum Woodland in the ACT than the 2004 mapping. However, there was also approximately 2000 ha of vegetation that was mapped in 2004 as Box–Gum Woodland, but classified in the 2011 mapping as not being part of the community. Thus, about 3700 ha of woodland was mapped differently in the 2004 and 2011 maps.

Woodland areas mapped in 2004 as Box–Gum Woodland, but not included in the total area of the community in 2011, mainly consisted of:

- 190 ha lost to urban development (mainly in Gungahlin)

- about 1200 ha of woodland in the Naas Valley and Murrumbidgee River Corridor south of Tharwa; this woodland occurs on ridges and steeper slopes above the Naas and Murrumbidgee valleys (such as Fitzs Hill) where Yellow Box may be present as a subdominant species, but the community is now classified as Norton’s Box (Eucalyptus nortonii)–dominated shrubby open forest

- about 350 ha of woodland along Uriarra Road, which now has some areas of cultivation and other areas where exotic perennial grasses predominate

- about 200 ha in the vicinity of central Molonglo.

The main areas of Box–Gum Woodland mapped in 2011 that were not included in the 2004 community primarily comprised:

- about 1600 ha of grazed woodland in the Murrumbidgee Valley, between Pine Island and the Tharwa Sandwash, where the ground layer is now dominated by native grasses

- about 450 ha in the proposed suburbs of Kenny and Throsby

- about 300 ha on the lower slopes of Mounts Ainslie and Majura, and about 275 ha in the Callum Brae and Isaacs Ridge nature reserves

- 260 ha in the vicinity of Uriarra Village

- about 200 ha in the Moncreiff, Taylor and Jacka areas of Gungahlin.

Box–Gum Woodland in Gungahlin

The Box–Gum Woodlands within Gungahlin are some of the largest, best-connected and most diverse patches of this vegetation type remaining across the former distribution of the community in south-eastern Australia. In the context of the distribution of the remaining Box–Gum Woodland, the Goorooyarroo – Mulligans Flat woodland patch north of Bonner is the largest area remaining in the ACT. Because of its high connectivity, size and diversity, this is a key area for maintaining functioning Box–Gum Woodlands. The woodland at Kenny is particularly notable in that it supports old-growth Yellow Box (300–450 years old), which are part of a Yellow Box on lowland valley flats (below 620 m) vegetation type that has been extensively cleared and now has a highly restricted distribution. It is noted that the condition of the woodland at Kenny is influenced by site quality; Kenny contains deeper soils and increased water supply due to its unique subsoil properties.62

Kenny also features small areas of Ribbon Gum adjacent to exotic grassland that was formerly part of the Natural Temperate Grassland zone. These small areas represent a rare and complete example of a lowland woodland to Natural Temperate Grassland catenary sequence (noting that the Natural Temperate Grassland is now largely exotic).62

Woodland condition in Canberra Nature Park

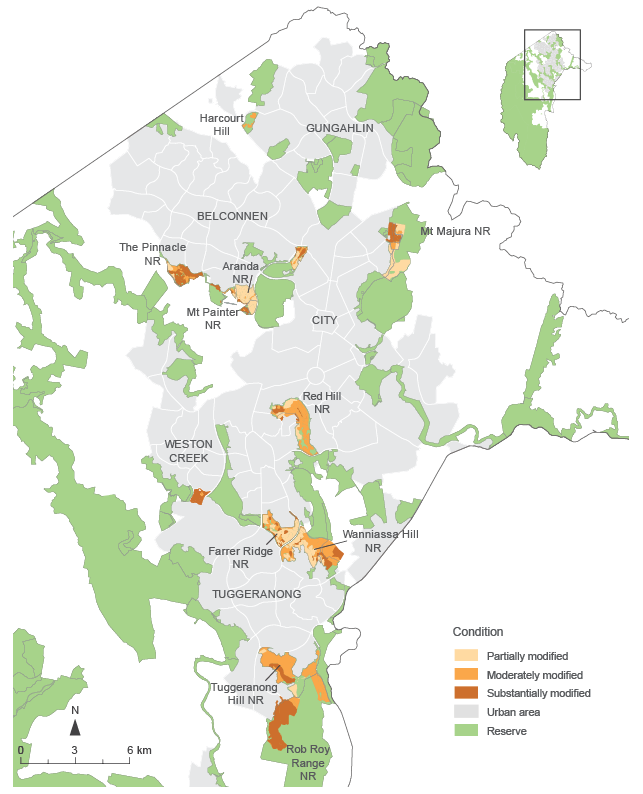

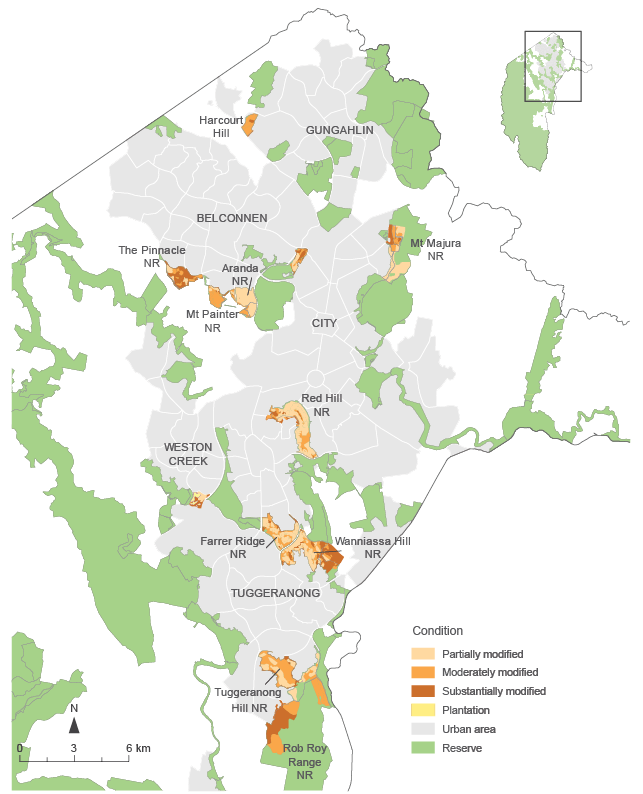

The condition of around 2145 ha of lowland woodland was mapped in separate surveys during 2001–2004 and 2012–13. These surveys were then compared.63

Figure 7.15 shows the condition classes mapped during 2001–2004, and Figure 7.16 shows the condition classes as remapped in 2012–13. Areas shown as blank in the 2001–2004 map, but coloured in the 2012–13 map, were exotic vegetation at the time of first mapping, but are now predominently native.

NR = nature reserve

Figure 7.15 ACT lowland woodland condition classes, 2001–2004

NR = nature reserve

Figure 7.16 ACT lowland woodland condition classes, 2012–13

There has been a general and significant improvement in condition across the surveyed lands during the approximately 10-year period between mapping exercises (Table 7.8). During this time, there has been a 52% increase in the area of land in the highest condition class and a 20% reduction in the area of land in the lowest condition class. The largest expansions of partially modified vegetation have been at Red Hill and Tuggeranong Hill. The greatest reductions of poor condition vegetation have occurred at Rob Roy and Tuggeranong Hill.

Table 7.8 Woodland condition change across mapped areas in the ACT, 2001–2004 to 2012–13

| Conditiona | 2001–2004 (ha) | 2012–13 (ha) | Change |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Substantially and severely modified |

712 |

567 |

–20% |

|

Moderately modified |

890 |

751 |

–16% |

|

Partially modified |

543 |

827 |

52% |

ha = hectare

a Condition assessment classifications:64

Substantially modified. Low to very low diversity of native species, mainly disturbance-tolerant native grasses, and usually a high cover of exotic perennial and annual species.

Moderately modified. Moderate diversity and cover of native species, but mainly disturbance-tolerant species. These species include Common Everlasting (Chrysocephalum apiculatum), fuzz weed species (Vittadinia spp.) and Variable Plantain (Plantago varia).

Partially modified. High diversity and cover of native species, including disturbance-sensitive species (eg lilies, tall daisies, orchid and pea species).

Note: A comprehensive list of disturbance-tolerant (or common) species and disturbance-intolerant (or significant) species can be obtained from Rehwinkel.65

Some care needs to be taken in the comparison of the results, because 2001–2004 were drought years in which vegetation was hard to assess, and the comparison is only between two surveys, rather than many. The exact cause of the observed improved condition is not known and likely to be a combination of many factors, including favourable seasonal conditions and some land management actions, particularly weed control. Nevertheless, a positive trend is evident.

There were 14 different sites mapped, 10 of which were located within Canberra Nature Park. The improvement in condition is slightly better if the reserve areas surveyed are considered alone (Table 7.9).

Table 7.9 Woodland condition change for reserve areas only, 2001–2004 to 2012–13

| Conditiona | 2001–2004 (ha) | 2012–13 (ha) | Change |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Substantially and severely modified |

506 |

368 |

–27% |

|

Moderately modified |

761 |

655 |

–14% |

|

Partially modified |

527 |

804 |

53% |

ha = hectare

a Condition assessment classifications:64

Substantially modified. Low to very low diversity of native species, mainly disturbance-tolerant native grasses, and usually a high cover of exotic perennial and annual species.

Moderately modified. Moderate diversity and cover of native species, but mainly disturbance-tolerant species. These species include Common Everlasting (Chrysocephalum apiculatum), fuzz weed species (Vittadinia spp.) and Variable Plantain (Plantago varia).

Partially modified. High diversity and cover of native species, including disturbance-sensitive species (eg lilies, tall daisies, orchid and pea species).

Note: A comprehensive list of disturbance-tolerant (or common) species and disturbance-intolerant (or significant) species can be obtained from Rehwinkel.65

Woodland condition on Red Hill

From 1990 to 2011, the condition of ACT-listed lowland woodland was mapped in relation to weed invasion and weed control. Weeds were mapped as to whether they occupied 50% or more of the understorey (poor condition), 50–25% of the understorey (moderate condition), 5–25% of the understorey (high condition) or less than 5% of the understorey (very high condition).

In 1990, weeds dominated 53% of the hill, and decreased to 13% in 2011 (Table 7.10). Correspondingly, in 1990, there was 21 ha of very high quality woodland on the hill, and in 2011 there was 131 ha (M Mulvaney, Senior Environmental Planner, Conservation Research, EPD, pers comm, 15 August 2015).

Table 7.10 Condition of woodland on Red Hill, 1990, 2004 and 2011

| Condition of woodland | Area 1990 (ha) (% of total) |

Area 2004 (ha) (% of total) |

Area 2011 (ha) (% of total) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Poor or substantially modified |

168 (53%) |

29 (9%) |

40 (13%) |

|

Moderate or secondary grassland |

71 (22%) |

26 (9%) |

114 (36%) |

|

Moderately modified (equivalent to either moderate or high in the 1988 and 2011 surveys) |

– |

174 (63%) |

– |

|

High |

56 (18%) |

– |

29 (8%) |

|

Very high or partially modified |

21 (7%) |

46 (16%) |

131 (42%) |

ha = hectare; – = not applicable

Vegetation of the Kowen, Majura and Jerrabomberra districts

The Yellow Box – Apple Box woodland and Yellow Box – Blakely’s Red Gum woodland communities are both components of the White Box – Yellow Box – Blakely’s Red Gum grassy woodland and derived grasslands listed under the EPBC Act, and Yellow Box – Blakely’s Red Gum grassy woodland listed under the Nature Conservation Act. At the time of writing, 8151 ha of vegetation in the ACT was regarded as meeting EPBC Act criteria, and 13 765 ha met the Nature Conservation Act criteria.60 Conservation reserves within the ACT contained 3364 ha of the EPBC Act–listed community and 5699 ha of the Nature Conservation Act–listed community.60

Grasslands

Extent of Natural Temperate Grassland

Natural Temperate Grassland is one of the most threatened natural plant communities in Australia. Before European settlement, such grasslands occupied 11% of the ACT. Today, they occupy less than 1% of the ACT, and what remains is degraded and continually threatened by human activity and invasion by exotic plant species.66

The once-extensive Natural Temperate Grassland within the ACT is now highly fragmented and greatly reduced in area. Grasslands are now confined to 38 small and isolated patches in the ACT. About 1000 ha of these patches are in a more or less natural condition, and a further 550 ha are in poorer condition. The patches of grassland are embedded in highly degraded grasslands dominated by weeds (plant species of exotic origin or native species not natural to the area). These isolated patches range in size from less than 1 ha to 300 ha.66

Natural Temperate Grassland is declared an endangered ecological community under both the EPBC Act and the Nature Conservation Act. However, Action Plan 28 only considers grasslands below 625 m to be part of the endangered ecological community, whereas the EPBC Act considers grasslands up to 1200 m to be part of the community. To date, 1049 ha of ACT grasslands below 625 m and 207 ha above 625 m have been mapped. For grasslands below 625 m, there has been a slight decline in the extent of the grasslands, from 1106 ha to 1049 ha. This change is mainly attributable to more accurate mapping, which excluded some native pasture in the Majura and Jerrabomberra valleys that had been formerly mapped as Natural Temperate Grassland.

Trends in grassland condition

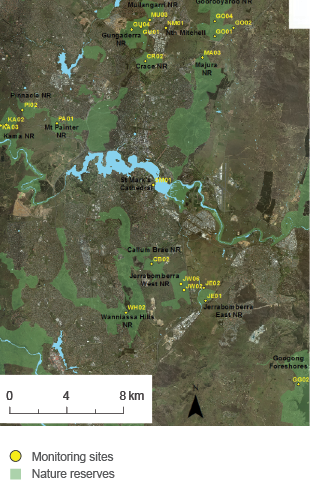

A 2014 research project examined trends in a range of floristic and vegetation structure attributes across 24 monitoring plots located in the grasslands and grassy woodlands of the ACT in 2009, 2012, 2013 and 2014 (Figure 7.17):67

- Overall, native species richness and the floristic value score (FVS),64 remained relatively stable (less than ±25% change) at most plots. Native species richness showed the least amount of change.

- Trends in the FVS were driven by the presence or absence of several indicator species. (Indicator species are grazing-intolerant or declining species. It is thought that these species are rare for two reasons. Firstly, some species have always been rare, particularly species that are restricted in distribution. Secondly, many species are thought to have undergone serious declines since European settlement, from disturbances such as overgrazing and fertiliser use.)

- Exotic species richness fluctuated to a greater degree, especially between 2013 and 2014, with two-thirds of plots showing more than a 25% increase.

- Cover of exotic annual grasses and exotic broadleaves also increased significantly between 2013 and 2014. Some sites had an increase in significant weed species richness in 2014, although numbers remained low.

- Plots that showed considerable declines in both native species richness and the FVS during the most recent survey period (2013–14) were Dunlop Nature Reserve, Jerrabomberra West Nature Reserve (inside the enclosure), the Googong Foreshores and Mount Painter Nature Reserve.

Figure 7.17 Location of surveyed plots across the northern ACT

Community case study 7.1 shows how groups in the ACT have been working to improve the state of the environment.

Community case study 7.1

ParkCare and Landcare groups in the ACT

For the past 25 years, ParkCare and Landcare groups have been working across the ACT’s reserves and urban open space network to improve the state of the environment. These groups provide an opportunity for enthusiastic volunteers of all ages, backgrounds and abilities to become involved in planting trees, controlling weeds, repairing tracks, monitoring the environment, protecting natural and cultural heritage values, controlling erosion and much more. They take pride in ensuring that their ‘local patch’ is properly managed and appreciated.

Friends of Aranda Bushland is one of more than 60 ParkCare and Landcare groups within the ACT. This group of about 60 members has been progressively rehabilitating the Aranda Bushland since the 1990s. A core group of 20 active members regularly carries out weeding and restoration works using planting, woody weeds, logs and ‘geofabric’ to reduce erosion and stop gullies from forming. Seed is also collected from the area, and used for propagation and planting. The group is working towards short-, medium- and long-term goals, and strives to educate the public through guided walks, interpretive signs and publishing Our patch – a photographic field guide to the flora of the ACT, now in its second edition. For the past 25 years, this group has achieved an almost complete reduction in weed infestation and, by planting locally indigenous Snow Gums, contributed to the restoration of Snow Gums in the Frost Hollow community.